According to Barry Nicholls, author of Second Innings, the language we use for mental health needs improvement

Mental health language matters and we all have to do better.

There’s been a lot of talk in the last few years about the way we use language. How it can cause prejudice. But what about the way we use language surrounding mental health?

More often than not it’s derogatory.

Social change is the constant, but not for those who have experienced poor mental health. In 2021, they are still more likely to be stigmatised to the point of irrelevance. Why? In part because of the language we use and the way it discourages openness. Words can indicate shame and cause secrecy where problems are not discussed.

In some ways it’s a self-fulfilling prophecy.

It’s a matter of ‘we don’t talk about it, therefore we don’t have it, therefore it’s not a problem.’ The stigma associated with mental illness remains strong. Government funding for mental health is inadequate.

All while the silent majority know the reality – at some stage you or someone you know will experience poor mental health. In the mid-1980s my eldest brother, Steve, who spent decades incapacitated by severe mental illness, said, ‘Mental illness is the bargain basement of discrimination.’

And it remains so.

We use words like ‘crazy, mad, nuts, unstable’ to describe people who are mentally unwell. They are emotive and wrong and lack compassion.

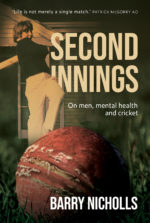

For my book Second Innings: On men, mental health and cricket, I was recently asked in a radio interview if attitudes toward mental health had improved.

I said I thought they had. But we still have a long way to go.

There’s a greater awareness.

We’ve improved at a ‘superficial, at a distance as long as it doesn’t affect me’ level. Remember the refrain from our parents? ‘Sticks and stones will break my bones, but words will never hurt me.’ Of course, it’s bullshit. Words and language, as we’ve seen from racism and homophobia, can have an enormous effect on lives.

When it comes to language surrounding mental health the medical profession needs to start leading the way. Terms like ‘schizophrenia’, ‘bi-polar disorder’ and ‘paranoid personality disorder’ are hardly going to be met with open arms and smiles. All they do is deliver a life sentence. I’ve seen the effect language and labels like this can have. For some, you may as well tell them to give up on life.

The late research scientist and medico Hazel Claire Weekes, who wrote simply and with clarity about anxiety and depression, used much gentler language. The word ‘depletion’ replaced ‘depression.’ ‘Repletion’ was used to describe recovery. My mother kept a copy of one of Weekes’ books called Peace From Nervous Suffering: A practical guide to understanding, confidence and recovery. Mum underlined passages and she used it to help cope with her own anxiety. Weekes used straightforward language. Not stigmatising language.

Change is needed. From us all.

Diversity is now one of the buzz words, and not before time. Diversity encompasses the need to include people who have suffered with mental illness. Especially those who suffer prolonged and extreme conditions.

My brother Steve was a physiotherapist but his confidence was so eroded by various mental health crisis and the stigma associated with it that he gave up. This was back in the 1980s and 1990s and if you think the mental health resourcing stigma is poor now you should have seen it back then.

Why is it that we use respectful language to describe medical conditions generally but not when it comes to mental health? It’s one the reasons people don’t seek help.

If you break your leg and end up in hospital, watch the sympathy, flowers, cards and visitors flow in. For those in mental health hospitals, all you’ll probably get is the sound of crickets and the gentle plodding of parents or siblings’ footsteps.

People often don’t know how to react to someone who has been diagnosed with a mental illness. We fear to tread so we don’t tread at all for concern of ‘invading someone’s space’. But what a person most needs when they’re recovering is kindness, compassion and support.

Mental health in the media is often treated more like a chance to grab attention with sensationalistic headlines than inform. The mentally ill who commit crimes are labelled ‘deranged’ or ‘mad,’ involved in ‘frenzied attacks’.

The statistics tell us that people with serious mental health illness can commit violence but it’s rare, and when it does happen it’s usually related to other factors (e.g. drug abuse, environment). Most often people with a mental illness will kill or harm themselves, not others.

Language matters.

Headlines such as ‘Managing Asia’s bipolar disorder’ to describe Australia’s power balance with Southeast Asia or ‘60 minutes of mollusc madness’ for a brief period of abalone fishing just add to the misconceptions. Yet I read both of these headlines in newspapers recently, one in a respected national daily. We haven’t really come that far, have we? And as for the misuse of the words ‘schizophrenic’ or ‘manic’ in the media or entertainment industries, it’s just ignorant.

If you change the language, you can change the thinking that alters the behaviour.

But first we need to change the language.

‘Walk a mile in my shoes.’

Let’s do better.

All of us.