Interview: David McComb’s Poetry

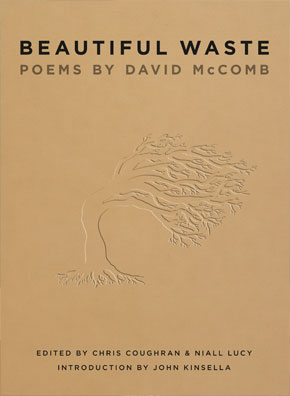

Emerging Arts Professional Kiri Falls talks to Chris Coughran and Niall Lucy about editing Beautiful Waste: Poems by David McComb.

How did you actually get hold of the manuscript?

NL: We were kindly given access to the manuscript during the course of working on Vagabond Holes. Our initial idea was simply to include a few of David’s poems in that book, but we soon realised there was enough material of sufficient quality to warrant a book in its own right.

CC: A few poems trickled through to us, piecemeal, appended to various contributions to Vagabond Holes. So Beautiful Waste is something of an afterthought, a ‘spin-off’, albeit one that rivals, if not exceeds, its progenitor in terms of cultural significance.

Were you previously aware of David’s poetry (outside of songwriting)?

CC: No, not at all – although the chances were always good. I mean, one likes to think, as a Triffids fan, of David’s songs as being somehow ‘poetic’ … But apart from one interview, given late in The Triffids’ career, McComb kept relatively quiet about his poetic aspirations. Only close friends and family – and perhaps also, it must be said, the occasional publisher – appear to have been privy to the photocopied collections of verse which, for McComb, remained utterly distinct from his prolific output of song lyrics.

NL: I knew David for many years and was aware that he wrote poetry, and also indeed short stories, which is why I was keen to find some of the poems for inclusion in Vagabond Holes. Then, as I said, we decided to bring out the poems as a separate volume. Perhaps his short stories will be collected one day.

Tell us about the process of selecting and ordering the poems.

CC: Niall and I decided early on to rule out the entire manuscript compiled while McComb was barely a teenager – even though its title page contained a clear enough instruction, typed all-caps and in triplicate: IF FOUND PLEASE PUBLISH. That collection of ‘juvenilia’, shall we call it, is yet to see the light of day – perhaps, we hope, as a hypertext or electronic edition.

As for the poems included in Beautiful Waste, these derive from multiple versions circulated among family and friends. To complicate matters, the manuscript provided by the McComb estate included David’s handwritten list of at least two alternative sequences, each divided into a different number of sections, containing a different number of poems, and so on … none of which made any particular formal or thematic or chronological sense. Rather than attempting to decipher what appear to be the author’s intentions, and wishing to avoid the other extreme of randomness or complete arbitrariness, Niall and I chose to group the poems loosely by theme, adhering where possible to sub-sequences identified in the materials supplied by the McComb estate.

NL: It was clear from the various manuscripts that David himself was struggling with this process, and that, in effect, he needed an editor, someone familiar with the business of ‘making a book’, as it were, and who could offer an independent perspective. We tried to retain traces of his own sequencing, where we thought the sequence had some kind of internal logic or integrity, but otherwise we opted to collect the poems around broadly conceived themes.

CC: Chronological ordering was always an impossibility based on the information available to us. A few poems are given a date of composition; others we can trace, in one variant form or another, to a date of publication, albeit in a fanzine that only a handful of people ever bought or read.

Which themes became apparent to you as you edited the collection, and why did you choose this arrangement?

NL: Love and loss, nature, and (my personal favourite) body parts.

CC: And – to borrow from our classificatory work on Vagabond Holes – a sense of the secluded or the unknown, or ‘unmarked tracks’.

NL: It’s not to say they couldn’t have been arranged otherwise, of course, but in the end we felt the divisions we’d imposed – or, as I prefer, created – helped to give the book a sense of shape that wasn’t contrived or determined.

How would you describe McComb’s nostalgia?

CC: Complex. Knowing. It seems to me that the idea of a ‘return’ home, or to some state of innocence, is always laced with irony or despair in McComb’s work. Bitterness, even. This is not to say that some semblance of such a return wouldn’t be a pleasurable, or more to the point, desirable experience, whether for McComb himself or for any of his characters.

NL: I’m not sure he was ‘nostalgic’, particularly. I’m not sure he was a voracious reader of contemporary poetry – certainly he wasn’t part of any poetry ‘scene’ as such – and I suppose you could say that the generally formalist nature of his work is a reflection of his interest in poetry, or in a way of writing poems, that isn’t terribly fashionable these days. But I’m not sure that makes his work ‘nostalgic’. Musically, however, far from being nostalgic, I think he was aggressively innovative and forward looking, although many of his reference points were artists and records from ‘the past’.

How about his uses of cliché and everyday language?

NL: He seemed to be inspired by everyday speech – colloquial expressions – found objects, as it were – that caught his ear and seemed to take his fancy. I’d say that most of his language games, in his lyrics as well as his poems, derive from a bit of slang or a familiar turn of phrase.

CC: McComb has always struck me as a writer with a gift for the vernacular. I think many of his earlier songs, in particular, play with cliché, and in doing so transform the banal uses of everyday language into something musical, something extraordinary.

Is there an intersection of music and poetry in this collection? If so, how would you read the musician in the poetry, or the poet in the music?

CC: I think poetry and music inevitably overlap; both have rhythm, cadence, and so on. But it was important to us that the book of poetry stood as a significant accomplishment in its own right, independent of McComb’s status as a singer-songwriter. Publishers and the media see this slightly differently, of course.

NL: We wanted the poems to be engaged with for their own sake. We think they show enough verbal dexterity and feistiness to warrant that. But of course many readers will scour them for signs of McComb’s interiority, and they’ll seize upon certain known biographical facts about him. He suffered from a lot of back pain and he had a heart transplant, so a poem like ‘Bad Back Bad Heart’ would be an obvious candidate for this kind of treatment. And that’s fine. Personally, though, I’d much prefer to know what readers who didn’t know anything about David’s life or his music thought of the book – just as I’m not all that interested in hearing what people who knew David personally think about Vagabond Holes.

CC: Ultimately, of course, it’s the reader who makes the connection between McComb’s poetry and music – or not, as the case may be. It was extremely reassuring, and indeed heart-warming, to gauge John Kinsella’s reaction when we first presented him with the poems, since he so clearly recognises a poetry manuscript – as opposed to somebody’s unpublished song lyrics – when he sees one. John, as it turns out, had been trying to track down David’s poems on the internet, and knew – not quite by heart, but almost – the few poems that had already appeared on Graham Lee’s website.

What are the influences – both literary and environmental – that you see in McComb’s work?

NL: David read widely, but in very, very broad terms you might say his literary influences were American prose and Australian poetry.

CC: His interests and tastes were eclectic. Occasionally, in the poems, there are direct allusions – to Dorothy Parker or Rilke, for example – but more often than not they are subtle. John Kinsella, in his introductory essay, identifies some plausible candidates. And John rightly, I think, points to McComb as a literary ecologist, one who imbibes and draws inspiration from a full range of cultural and environmental phenomena: the high and the low, the beautiful, the ugly.

NL: I guess by ‘environment’ you’re referring to the fact that he grew up in Perth, and there’s no doubt that he was ambivalent towards the middle-class Perth suburban ‘experience’ of the 1970s. But everybody comes from somewhere, and I don’t know that sometimes too much isn’t made of the fact that David came from Perth. Certainly I don’t think his work is reducible to the ambivalence he felt towards the place. I mean, Kant spent his entire life in a little German town, but nobody reads that into The Critique of Judgement!

CC: Again, though, it is the individual reader’s prerogative to make connections for themselves between McComb’s writings, various landscapes or literary texts. Or not, as the case may be.

Do you have a favourite poem? Which one, and why?

CC: I like ‘The Joy of Loving’ because it’s so easy to remember; an ‘aphorism for every occasion’ – the levity and brevity of which insures us against so much existentialist angst.

NL: I like the ‘body parts’ poems. I’m a big fan of abjection.