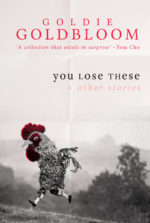

INTERVIEW: Goldie Goldbloom

Get to know a little more about Goldie Goldbloom.

What things can you do with a short story that you can’t do with a novel?

Read it in the bath in one go without having to change the water. Burn it easily. Turn it into a paper aeroplane that sticks nicely in your physics professor’s beard. Wedge it under the kitchen table to stop the wobbling. Go broke by writing it instead of a novel. Use it to wipe your bum if you are out in the bush without toilet paper. Colour it all in black with a crayon. Download it online without losing all those photos you were saving from the office party in case you needed to blackmail someone. Remember most of it when you tell it to your bestie over the phone. Roll up bits of it to turn into one of those dangly screens that stop the flies coming in. Use it to line your cockie’s cage. Fake having read it when your teacher asks if you’ve done your homework. Pop it in the microwave under a slice of pizza. Swallow it if you are interrogated as a spy. Send it through the mail without mortgaging your firstborn child to Rumpelstiltskin.

Who are your favourite short story writers and why?

It’s a cruel world where you are asked to pick amongst your favourite children.

They are all my favourites. All of them. Every time I read a good short story, I yell out to my kids and say, “I just read the best short story I’ve ever read!” and they call back “You said that last time!” and it’s true.

But some writers who I’ve come back to again and again are Jim Crace, William Trevor, Eudora Welty, Anton Chekhov, Angela Carter, Lydia Davis, Antonya Nelson and the one, the only, Alice Munro.

But for sheer delight, a dear dear friend of mine, Ray Daniels, who I am convinced will one day win the Nobel Prize.

Why did you choose the title You Lose These for this collection?

Ha! I didn’t. I’m completely crappy at selecting titles for my own work. I tend to choose things that sound like I was abducted by aliens and had Muppets surgically implanted in my brain. I’m pretty fortunate in having Georgia Richter at Fremantle Press as my editor. She reins me in and insists that “Dorkface City and the Fungal Outcropping at the Rubbish Tip” is inappropriate for serious literary fiction.

I love You Lose These as a title because it encompasses a lot of what I was trying to say in this collection. The losses we accrue in life are the impetus for many of my stories.

And, bonus! It makes me sound like I’m making a spoof of Ulysses. Which must mean that I’m really smart and have probably read it…

In the book’s acknowledgements you write that ‘this is a book about folks not finding love, not loving themselves, or not being able to give love.’ Why is lovelessness important?

There are very few fiction writers today writing about happy couples, with the possible exception of Charles Baxter, who does it brilliantly, the evil genius. There’s a reason for the lack of happy couples in stories. When you are happy, there’s nothing to propel a story. “I love you!” “I love you better!” “No, I love you more!” “Well, I love you to the moon and back!” It gets boring fast.

So I write about the opposite of love, in the same way that an artist will use negative space to define what is real and tangible and important. Love is the most powerful human emotion. It’s profound and transformative and often excruciatingly painful. Good short stories have many layers, some visible and some not visible, and some which are like harmonics played on a harp, distant, unearthly echoes of our own lives. So what I’m really writing about is love, our very human desire for love, but it sounds like a distant bell. You’re not sure if you really heard it or not. Lovelessness is what is in the words.

The stories in this collection showcase a tremendous diversity of characters. Don’t you ever run out of ideas?

I run out of milk a lot. And bread. And fresh undies. But I have a mind that likes to traipse all over the joint and cavort in odd locations. Most people call this being wildly disorganised or, at best, being a space cadet, but I prefer to think of it as researching. And I take really weird jobs and befriend eccentric people, just so I can see and hear freaky stuff.

Believe that and I have a bridge I’d like to sell you too.

Can you give an example of how an idea of yours developed into one of the stories in this book?

At least three ideas need to crash into each other for a story to interest me. The ideas can’t be too similar; they have to exert pressure on one another. When I was thinking about ‘The Telephone of the Dead’, I had been wondering for a while what would happen if God let people who had died suddenly, slowly disconnect from their loved ones over a year. Would it be better or worse? And at the time, I was working in the Chevra Kaddisha, a Jewish group which prepares dead bodies for burial and someone mentioned the Midrash that God lets people out of Hell on Friday afternoons, and then I was visiting a friend and she has this funny collection of British phone booths and it reminded me of Doctor Who, and then, the image that tipped the scale and led to the actual story, was when a complete stranger began telling me how her husband was hit by lightning several times but lived. I can’t explain how all of these ideas came together to create ‘The Telephone of the Dead’ but all of them struck me in the particular way that I associate with the aha-moment of storiness.

What’s next for Goldie Goldbloom?

If you are offering chocolate, it’ll be chocolate, thanks.

But if not, well then, I’d best be getting back to my next novel, ‘The Bearded Lady Falls in Love’. By now, I hope you realise that there will never be a novel with that title published by me, if Georgia has anything to do with it. Instead, it’ll probably be something called ‘Communal Thinking’ or ‘The Walking House’ or ‘The Sodomist’s Tale’. Sorry. That last one was probably me talking again.