INTERVIEW: Renee Schipp, Curator of Thonglines

Renee Schipp is the co-curator of of Thonglines – an art installation to be launched at Voicebox on Monday 4 July. In this interview she describes the ‘Thonglines’ project and her work with mainstream students and refugees on Christmas Island.

My job on Christmas Island is to teach new arrival students, that is, refugee students arriving by boat on the island. It is a dynamic job with the age and nationality of the students varying depending on who has recently arrived, and it is common for students to be transferred to the mainland with little or no notice. It is certainly never boring!

I moved to Christmas Island specifically because I love working with refugee students, and I felt my skills and strengths would be well utilised with students who were ‘straight off the boat’. However, I cannot pretend that part of the lure was not the idea of working on a stunning tropical island with diverse cultural groups and over 60 percent national park, predominantly rainforest.

You cannot help but to be struck by the sheer number of thongs that wash up on the beach here, I guess mainly from Java. It is something distinctive about the island that expresses its unique geographical location. Christmas Island has no original inhabitants, so we have all ‘washed up here’ one way or the other, and I believe the fact that the island has only been inhabited for around 100 years makes the local population generally welcoming of new arrivals, and gives it a distinctive openness. Like the thongs, all us humans here have a common form but the imprint we make upon that form is unique and tells a story.

With the refugee people here there is also another layer. People do struggle to be as open to asylum seekers as they are to others who arrive by more ‘legal’ means. I think of the way Australians tend to try and ignore, sometimes shun, the things they find difficult, even the ‘refuse’ of war and intolerance. However, like our thongs, what is most confronting can actually be something of great potential and beauty if we have the will to see it.

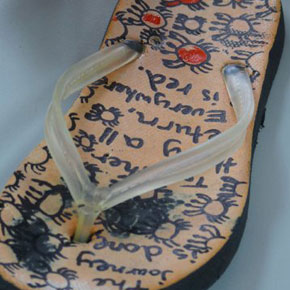

For ‘Thonglines’ we focused on haiku-inspired poetry because haiku often depicts nature, so it seemed fitting to the context of a tropical island. Our medium, writing and painting on thongs, also had the inadvertent benefit of helping to clean up our local beaches!

Haikus are a short form of poetry so, from a practical viewpoint, it meant the pieces were much more likely to fit onto a thong-sized space. However, for the mainstream students in particular, learning the potency of language was an important part of investigating haikus. Distilling some of our most important experiences down to around three short lines and learning an economy of language helped us tap into the heart of poetic writing.

Around forty students participated in the ’Thonglines project, with around half the students being local residents and the other half being refugee students living on camps on the island. The camps are demountable type buildings surrounded by fences and security that house families and unaccompanied minors. Children from the Island came from predominantly Chinese, Malay and European backgrounds while the refugee students were mainly from Iran, Afghanistan and Vietnam.

The main challenges when working with asylum seekers were firstly having no interpreters (and therefore sometimes no shared language) and the fact that the students are transferred quite suddenly. Halfway through the Thonglines project around half of the students were transferred to the mainland.

I don’t know what happened to most of the refugee students since working with them. That is the nature of our jobs. It is great when you get an email so you can hear how the students are going. Many of the students are sent to Darwin or Leonora while they continue to wait for their applications for visas to be processed.

The most rewarding part of the Thonglines project was being able to spend time with each individual student, giving them the whole of my attention and learning something unique about the way they see the world. It’s stimulating to be continually surprised by the way in which we are all so similar and yet so unique. Seeing the finished thongs all together was very satisfying; the kids loved to read each other’s work and biographies, which from a teaching perspective is an ideal learning environment.

Doing the Thonglines project was a deeply moving process in a way that I had not anticipated. The layering of the refugee student’s stories, even students I thought I ‘knew’, was so humbling as many traumatic scenes were shared but always without drama or self pity. At one point 60 Minutes walked into the camp with their camera and I couldn’t help but think ‘why aren’t you telling these stories?’

One moment in particular has stayed with me through this process. An Afghan teenager had written a short, sad poem, and I asked him whether he was going to include a picture with his thong. He took a piece of paper and began to draw a scene for me of women sitting together watching children play cricket in an open space. But then the student began to draw trucks and armed men, and he then demonstrated that the armed men had opened fire on the women and children by the roadside. He said, ‘I just stood there. All the children fell down, some dying and the women too, and I am just standing over here watching it all happen. I still don’t know why.’

The dismay expressed by the Afghan student was not uncommon amongst the teenage boys. All around sixteen or seventeen years of age, many of the older students seemed completely dismayed by the circumstances that forced them to leave their home and the people they love.

Personally I have learnt the very simple but profound fact that asylum seekers, like us, are just people. And they are often people who have suffered an enormous amount, and continue to suffer as they wait for some certainty in their lives. I have never felt threatened or disrespected my refugee people even when teaching all-male classes. Refugee people are also often people with deep connections to their families, but their will to survive and to be whole people has forced them to take enormous risks, both for themselves and for those they love.

What I hope the general public will learn from the Thonglines exhibition is to respond with their hearts, not just to headlines, when considering the plight of asylum seekers. So long as refugee people are locked or hidden away, Australians are able to imagine their worst fears rather than have any direct experience of refugees as real people.

With both mainstream and refugee students I took essentially the same approach. We looked at different examples of haiku (there are some great resources on the web now including visual works and student sites). I then asked students to use a similar short form to share something unique about themselves or their experience of Christmas Island. Some of the refugee students had very little English so they did remarkably well produce even the simplest poem. With these students it was a great way to explore syllables, and with all classes the project gave us a distinct purpose and a real audience, which for many students was clearly very motivating.

The mainstream students wrote their poems first so it was great for the refugee students to see their work as a model for their own. The refugee students’ work will go on display for Refugee Week at the secondary college on Christmas Island and I think this will be really important for our school to read the stories of students within the campus that they may not otherwise have the opportunity to hear.

Living and working on Christmas Island has been a gift. My job is intense and rewarding, then we go down to Flying Fish Cove in the afternoon where massive plate corals stretch out along the sea floor saturated by the intense blue hue of the water, while turtles and reef sharks eye us as they swim past. In the evening giant frigate birds soar on the updrafts over our home and bright red crabs weed the garden. We leave the keys in car, the house unlocked … it’s a pretty privileged lifestyle …

I would like to say thank you to Fremantle Press for believing in this project and giving the chance for all our students to have their voices heard. I would also like to thank he Christmas Island District High School staff for being so patient, supportive and flexible to make it all possible. Finally I would like to thanks the students for their openness to the project and for their willingness to share their stories.

Thonglines is on display at Clancy’s Fish Pub throughout the month of July for Fremantle Poetry Month. Join us at Voicebox for the launch at 7.30pm on 4 July 2011.

Biography

Renee Schipp is a teacher with over ten years experience in education, her work as an English as a Second Language Teacher taking her to locations as diverse as Indonesia, Perth, the Kimberley and Indian Ocean Territories. In 2007 Renee was awarded the Fremantle–Peel Award for Teaching Excellence and Innovation, and in 2009 was promoted to Level Three status for her exemplary teaching practice. Renee presently works on Christmas Island where she teaches English to refugee students and creative writing within mainstream classes. Renee’s desire to teach creative writing was born from her own writing practice. An active poet and travel writer, Renee’s writing has been published widely in magazines and journals such as Westerly, Landscapes and dotdotdash. In 2010 Renee was shortlisted for the Trudy Graham Biennial Literary Award and in 2011 she won the Ethtel Webb Bundell poetry prize.

SPONSORS

Fremantle Poetry Month is sponsored by Australian Poetry, dotdotdash magazine, Fremantle Arts Centre, the Fremantle Children’s Literature Centre, the Fremantle Library, Fremantle Radio, Thompson Estate, Out of the Asylum Writers Group, Voicebox and WA Poets Inc.