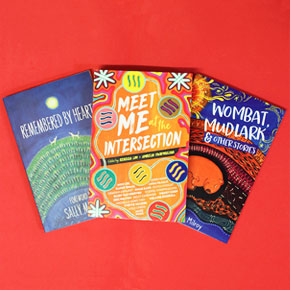

Three free extracts from Fremantle Press titles to use in your classroom this NAIDOC Week

NAIDOC Week takes place in the first week of July each year, which this year is Sunday 7 to Sunday 14 July 2019, and recognises the culture, history and achievements of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. It’s a great opportunity to show support for your local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.

The NAIDOC website has many suggestions about how you might celebrate the week in your school, but one that we can help you with is to read the work of an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander author. To get you started, we’ve made three exclusive extracts from Indigenous writers available for use in the classroom.

Junior readers, ages six to nine

Helen Milroy is a descendant of the Palyku people of the Pilbara region of Western Australia, but was born and educated in Perth. Helen has always had a passionate interest in health and wellbeing, especially for children. She studied medicine at the University of Western Australia and specialised in child and adolescent psychiatry. Helen is currently a Professor at the University of Western Australia, Consultant Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist, and Commissioner with the National Mental Health Commission. Helen was recently appointed as the Australian Football League’s first Indigenous Commissioner. Wombat, Mudlark and Other Stories is her first book for children.

‘Wombat and Mother Earth’ from Wombat, Mudlark and Other Stories by Helen Milroy.

From a falling star to a lonely whale, an entertaining lizard to an enterprising penguin, these Indigenous stories are full of wonder, adventure and enduring friendships. Told in the style of traditional teaching stories, these animal tales take young readers on adventures of self-discovery and fulfilment.

In this story, ‘Wombat and Mother Earth’, Wombat uses stories to warm Mother Earth, who in turn offers him refuge from the cold air with a burrow in the ground.

Since the beginning of time, Mother Earth had looked after everything and everyone, asking for nothing in return. Mother Earth had helped the trees to grow, the flowers to bloom, the animals to live and the rivers to run. But now that everything was thriving, everyone forgot about Mother Earth. Mother Earth was sad and lonely. She felt empty and cold. Although the sun came up every day to warm Mother Earth, by sunset, the warmth had already left her like a willy-willy disappearing into the sky. One night, Mother Earth was so cold she started to cry. Wombat was fast asleep under a tree and woke abruptly from his dreaming.

‘What is going on?’ he asked. ‘Who is that crying?’

‘It is me,’ said Mother Earth. ‘I am sorry I woke you but I am so cold and sad, I can’t stop shivering. I don’t know what has happened to me but I haven’t felt happy for a very long time. I don’t know what to do,’ she sobbed.

‘Oh dear,’ said Wombat, ‘let me see if I can help you.’

Wombat felt very sorry for Mother Earth. He had never seen her like this before. Wombat loved Mother Earth and all the wonderful things she had helped to create. So Wombat started to tell Mother Earth of the many beautiful discoveries he made each day and of the wondrous dreams he had every night. He told her how much he loved and cherished her.

‘None of us would survive without you,’ said Wombat.

Wombat and Mother Earth talked and laughed together until the early hours of the morning. Wombat was so pleased to have someone to share his stories with and Mother Earth loved hearing them.

‘I am no longer feeling so cold,’ said Mother Earth. ‘For the first time in a long time, I feel warm and happy.’

‘That may be so,’ said Wombat, ‘but now I am freezing after sitting up most of the night!’

‘Dig a deep burrow into the soft earth and I will keep you warm and safe in my belly until the sun wakes up for the day,’ said Mother Earth.

Up until that night, Wombat had always slept on top of the ground. Each night he tried to find some soft leaves or a warm place to sleep. Sometimes it took ages for Wombat to find the right spot and this shortened his dreamtime. Sometimes when the sun woke him up in the morning, he hadn’t finished his dreaming and would wake very grumpy. Wombat was excited at the idea of sleeping in the belly of Mother Earth, it would be warm and cosy. Even the pesky sun wouldn’t be able to wake him up and he could dream as much as he liked.

‘That is a great idea,’ said Wombat who was now exhausted and desperate to return to his dreamtime. Wombat dug the burrow deep into Mother Earth and fell into a strange sleep. Each breath Wombat took tickled Mother Earth’s belly and Mother Earth giggled, but when Wombat snored, Mother Earth laughed out loud. Mother Earth was feeling warm and content looking after Wombat, while Wombat felt snug and safe in his burrow. Soon Wombat started to dream and something magical happened. The power and wonder of Wombat’s dreams swirled around Mother Earth’s belly and filled her with love, joy and hope. Mother Earth could now see clearly once again and realised what was wrong.

At the beginning of time, Mother Earth was born with an eternal flame buried deep in her heart underground. The flame had started to falter and her heart was struggling. Mother Earth was exhausted from always looking after everyone else. Now she needed someone to look after her.

The love and wonder from Wombat’s dreams were exactly what Mother Earth needed. It surged like electricity along invisible threads that wove through her, awakening the eternal flame and creating a furnace that warmed her completely. Mother Earth’s heart started to glow and its beat grew stronger and stronger, setting in motion rivers of light that radiated throughout Mother Earth. It was like the dawning of the first day, when hope broke through the darkness and the future became possible.

Through Wombat’s dream, Mother Earth was able to see all of what she had helped to create and how much love there was in the world.

Mother Earth was so grateful, she made sure Wombat was safe and sound until he awoke to start the new day full of stories yet to be told. Mother Earth even kept the sun from shining into the burrow until Wombat had finished his dreamtime.

In the morning Wombat woke feeling refreshed like never before.

‘That was the best dreaming I have ever done,’ said Wombat. ‘I am going to sleep in my burrow every night from now on! I am also going to make sure everyone looks after you as they should!’ exclaimed Wombat.

‘That would be wonderful,’ said Mother Earth. ‘I promise to watch over you every night so you can dream your dreams for everyone!’

Mother Earth never felt cold and sad again, and Wombat never again woke up grumpy. Mother Earth and Wombat loved sharing the stories and dreams together.

Every night, Wombat crawled into his burrow ready to begin his dreaming.

Every night, Mother Earth watched and waited for the dreaming to begin.

Middle readers, ages nine to 12

David Simmons was born in Perth to parents from the Nyoongah language group of south-western Australia, but has lived and worked in Roebourne for most of his adult life.

‘Hiding’ by David Simmonds from Remembered by Heart edited by Sally Morgan.

Content warning for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island people: This extract features people who are now deceased.

In Remembered by Heart, 15 true stories tell of a diverse range of Aboriginal Australian experiences, from life in the desert to growing up on a mission, enduring devastating policies in the 1930s to bravely seizing new opportunities in the 1960s.

In this extract, David details his school days, hiding from the Native Welfare Officer who threatened their community.

I was born in Subiaco, Perth. My mother is an Aboriginal woman from Kukerin in the Lake Grace area of Western Australia. My father came from the Margaret River area. He is an Aboriginal man. My stepfather is part of the Isaacs family from Perth. My parents are Nyoongahs.

My schooling as a young fella was undertaken at different places. Our family used to travel around a lot then.

In 1951 the Native Welfare Officers were still active. My younger school days were occasionally spent hiding from the Native Welfare. My mother insisted that I go to school, but there was always that dread that I would never come home from school because of Native Welfare. We knew that if Native Welfare ever found out that there were Aboriginal kids like myself at those schools, they would take them away. Native Welfare didn’t necessarily go and tell the parents that they had taken their child. We were all vulnerable to Native Welfare, who were always grabbing Aboriginal kids. I started school in 1950. I would turn six in June so I had to start when I was five and a half years old. It was at a very small place called Parkerville. I’ve been back since, taken my kids, it’s just a one-room building.

Parkerville is up in the Darling Ranges, not far from Mundaring. We shifted there as the old man, my stepfather, was a returned soldier working at Hollywood Repatriation Hospital in Perth. Some of the old returned soldiers had country properties. He used to negotiate with them. The family had to keep out of the way of the Native Welfare because Mum wouldn’t give up her Aboriginality.

Not long after I started school we shifted to Mount Helena. It is another very small place back in the hills around Perth. I used to catch the bus to school myself. The school building there was the town hall. Quite a few kids went to the town hall. There was more than two busloads, all mixed up, but I was probably the only Aboriginal kid at school. I can remember my mother taking me to school and asking the teacher, if the Native Welfare were to come, would they hide me?

I remember that on several occasions that a Scottish teacher called Miss Lang raced into the class and grabbed me saying, ‘Quick, quick, come in here.’ And she got another boy, who is my friend to this day, to go with me and hide under the wooden stage. So we ran and hid under the stage. She said, ‘Don’t you kids come out until I tell you.’ The Native Welfare man came in and asked if there were any Aboriginal children at school and the teacher said, ‘No.’ It was probably an hour or so before we could come out.

On another occasion we were out in the yard playing when the Native Welfare officer came. She told one of the kids to get me and go up under the hall. We had to climb right under the school. A few of the kids came with us and they thought it exciting hiding under the school until the Native Welfare bloke went. But it wasn’t a prank for me. I think these visits were a response to someone dobbing me in, but I’m not sure.

But we were dobbed in on a couple of occasions when we were at Parkerville because the bloke came to our house. But we had a system. Mum set it up. There was a tree two hundred metres away from the house and another about five hundred metres away. She would leave bottles of water under the trees. The system was that if the Native Welfare came we were to rush to the first tree and stay there. The dog was to come with us and he wouldn’t let anybody come near without barking a warning. If the dog barked a warning and it wasn’t Mum yelling out, then we would go to the next tree which was further out and hide there. We had about half a dozen bottles of water that we would take with us and Mum would give us some bread or damper, whatever she had, and we were off. I was the eldest. We all had fair skin. Clarrie has got the darkest skin of all of us.

Native Welfare would have just grabbed us. My elder brother and sister were in Sister Kate’s children’s home. Mum put them in Sister Kate’s so she knew where they were. In this way she could stop Native Welfare efforts to grab kids. She put Alice and Bill, who are older than me, into Sister Kate’s. Sister Kate’s at the time had a lot of half caste kids.

Unfortunately Native Welfare took the kids from the south and sent them north. They took kids from the north and brought them south. They crossed the people up all the time.

Mum always taught us about little things when we were kids in the bush. How to track rabbits, know the difference between the animals, how to catch the animals, where to look for them all and which animals we could eat, those sorts of things. The old man worked at Hollywood Repatriation Hospital. He only came home four days in a month. He didn’t have a vehicle to drive home every weekend. We wouldn’t see the old man for months at a time. What he would do is try to work for three months and then get twelve days off. In this way he had some sort of time off especially when we were on holidays.

So we spent a lot of time at home with Mum. It was really good. She always taught us to respect our elders, which I always follow. When we moved to East Perth we were among a lot of Aboriginal people who were like fringe dwellers. We never turned the people away and we were never afraid to mix with them. I certainly was never afraid of the people. Those were the things that my mother passed on.

Then there was the Coolbaroo League, it means black and white magpie. Back in ’55, ’56 it had a little meeting place in Murray Street. It was the Young Men’s Christian Association, I think. They had a lot of the old people come in there and sit down and tell us stories. In those days they still brought in the traditional spears and shields and boomerangs to those meetings. They used to have a lot of arts and crafts there to sell. Not so much art but craft. We heard all the stories about why the crow was black, how the red robin got red, how the emu and the goannas swapped feathers and all of those stories.

I was never part of a corroboree, never went to one in those days. But there was an elder, Bill Bodney. He was the old tribal top man back in the 1950s, responsible for Perth. I remember to this day when the Queen came, she had to be given the boomerang of peace by old Bill to say that she could come to his country, because that was his place. He was on the airstrip when she came to Australia.

I finished my primary school in East Perth and I went on to high school. It was for boys and I left halfway through the second year, as soon as I turned fourteen. In those days you were allowed to leave school at fourteen. I could have gone on to do wonderful things. I was told by the headmaster that I would have made an excellent accountant. But in those days, you had to know somebody who could get you into accountancy. We didn’t have those sorts of contacts.

In those days there was plenty of work around for young blokes straight out of school. I started off working with my brother in a timber mill just up the road from us in Charles Street. The Tower Hotel was on the corner. The old fella next door had a little bit of a timber yard at the back and I worked there for about a year and a half. Then I left and went and worked for an old fella in a nursery.

At this time we’d moved to West Perth. I left school in 1959. We were there for only a short while and got our first State Housing house in Barney Street, Glendalough. Later, I was the last member of the family to live in that house. We lived there until 1986.

Once we were in that house in West Perth, Mum set it up as a halfway house for the kids coming out of Sister Kate’s. There was a need which she saw. Kids coming out of Sister Kate’s had nowhere to go when they turned fourteen or they finished high school, because then they had to get out.

Not far from us, on the corner of Fitzgerald and Carr Streets, was a place called McDonald House. McDonald House is part of the Aboriginal history. They taught the kids, in a TAFE type situation, to do things like bookkeeping, accounting, etc. It was the first sort of Aboriginal access in Perth. There were limited numbers of kids getting places there, so Mum set up this halfway house. No government funding, just did it off her own bat. The kids who wanted to get into there came and stayed at our place. We had a big four-bedroom house. Mum put beds in, about four or five kids in each room like a little dormitory set up.

They stayed with us. There was plenty of work around so they were able to support themselves and they had a place to come home to, three meals a day or prepared lunches. Then as places became available in McDonald House they went there and they were able to go on with schooling. That worked really well. Mum certainly made use of her time.

Abridged from Karijini Mirlimirli, edited by Noel Olive, 1997

Older readers, ages 14+

Ellen Van Neerven is a Yugambeh writer from south-east Queensland who now lives in Melbourne. She is the author of the poetry volume Comfort Food (UQP, 2016) and the fiction collection Heat and Light (UQP, 2014), which won numerous awards including the 2013 David Unaipon Award, the 2015 Dobbie Award and the 2016 New South Wales Premier’s Literary Awards Indigenous Writers’ Prize.

An extract from ‘Night Feet’ by Ellen van Neerven from Meet Me at the Intersection edited by Ambelin Kwaymullina and Rebecca Lim.

Meet Me at the Intersection is an anthology of short fiction, memoir and poetry by authors who are First Nations, People of Colour, LGBTIQA+ or living with disability. The focus of the anthology is on Australian life as seen through each author’s unique, and seldom heard, perspective.

In ‘Night Feet’, a soccer-mad Indigenous girl is trying to win a football scholarship, but is also desperate for her dad to see her score a goal.

There were more people outside the library than in, sitting at the café, standing against the walls talking and hooked into the wi-fi. I hurried through the doors, printed my application and went straight out, with minutes left to post it.

It felt familiar, running to the post office just before closing, across the road, under the bridge, past the pubs starting to get busy and noisy. I didn’t like running in my thongs, the V slipping between my toes, but I looked straight ahead and tried to think of an end goal. Like I was on the pitch.

The footpath was blocked off a little farther on, but there was no way I was going to cross the road and back again; I’d lose too much time. I dodged some parked cars and stepped over a patch of water that hadn’t drained, and got back on the footpath. Ahead of me, a woman dropped a letter in the express post mailbox outside the post office and I wondered if it was already too late. I half-expected the sliding doors not to open. I ran in and looked frantically around for an envelope. The lady behind the counter said, ‘Just a letter? Try an envelope from over there, honey.’

Not just a letter, my inner voice insisted, but I listened to her, and into the kind of happy cream decorative envelope you’d use to send photos of your cat to your grandmother — not the most important document of your life — I folded the application. I scribbled the address from a Post-It and handed the envelope to the lady.

‘Just this one?’

‘Will it be postmarked today?’ I blurted.

‘Ah, yeah,’ she said. ‘I just got to push this back.’ I watched her keenly as she picked at the mail stamp, clicking the numbers back. I realised that today was the last day of the month, and that the 28th to the 1st was a big leap. She seemed to struggle with it. Mum could have stood there, where the lady’s feet were. She changed the date, stamped my envelope, and I paid her.

I had half an hour until the train to the soccer field and I walked back to the café at the library. I ordered myself a coffee. I’d never had coffee before, but after a sleepless night and with the need for a load of energy tonight, I thought it was a good time to start. I did worry about dehydration, but I had two water bottles, and they could be refilled. With Dad’s voice, I said, gruffly, ‘Cappuccino, thanks.’ I ordered it to go, as they looked like they were packing up. I’d be the machine’s last kiss. When they handed it to me, I went and sat in the garden, and watched the people. There was a young black man, African, walking around. I admired his red, new-looking sneakers, a pair like the ones I wanted but Dad would never give me. I could hear the beat of his music, see the yellow buds in his ears. He was wearing a white T-shirt and grey jeans. He looked at me. I sculled the coffee, hot and sudden in my throat. My father’s habit. Mum always said to him, You burn yourself. You’ll have no tastebuds left for my casserole.

The coffee tasted nice, and I already felt less tired. There was a breeze filtering through the garden, caressing my thighs. I chucked the cup in the bin and decided it was time to get changed into my football shorts in the toilets. I stopped for a moment, reopened my bag and took a sip from my water bottle. ‘Keep sipping before the game,’ Brisbane Roar captain Jade North had said when he came to visit the club. ‘Don’t gulp.’

I loved North. I rarely had affection for a defender but I loved him because he was a blackfella and a real workhorse. I rested my bag on the slab of concrete on the side of the café. A sitting spot tucked away. This was the corner where I’d had my first kiss, last year, and the feeling of it always returned. I put my bottle down, and the wind picked it up and took it, and it rolled in the direction of the African boy. He caught it easily and handed it back.

‘Thanks,’ I smiled. ‘Crazy wind, hey?’

He nodded. He still had his earphones in but I couldn’t hear the music anymore. As I packed my bag up, he took a step closer and said, ‘Hey, how you going?’

‘Good,’ I said. ‘And you?’

‘Good. Just waiting for friends and that. Where are you from?’ he asked.

I half-smiled at the predictability of the question. The easy answer, and what felt true, was to say, ‘From here’.

But they always wanted to know more. He didn’t buy it, licking his lips.

‘My mother’s Italian, my father’s Aboriginal.’

‘Ah,’ he said, and repeated it for clarity.

‘And where are you from?’ I asked. It was only fair.

‘I’m from West Africa,’ he said, guarded, and of course it was a line from him. What was West Africa?

‘What’s your name?’ he said, looking at me with some sort of understanding.

‘Bella. Yours?’

‘Akachi,’ he mumbled self-consciously.

It took three times to pronounce it properly, but I wanted to. I looked in his eyes.

‘I asked because you look different,’ he said.

Again, I could have rolled my eyes at the predictability. We looked at each other. I was used to these sorts of moments of connection. Lines of dialogue came in to my head. Welcome, brother. Thank you, sister.

‘You study, work?’

‘I’m still at school,’ I said. How old did this fella think I was?

‘Oh. Yeah. I study and work.’

‘You doing anything interesting tonight?’ I asked.

‘Waiting for friends. We’re going out to the city. I go here to check my emails. You here often?’

‘Not really.’ I reckoned I should come here more often. ‘I’ve got to get changed,’ I said, pointing away.

‘Okay,’ he said. ‘Nice to meet you.’ And he made the effort to give me one of the handshakes I’d always wanted, made me feel like one of the boys.

In the bathroom I stood in front of a mirror. I slipped off my singlet and T-shirt bra. My arms were tanned from all those afternoons running in the bush. My small breasts, that I had just noticed a year ago, but my grandmother had obsessed with years before, were pale in comparison. There was a sunburnt strip across my collarbone from the last game. I was still kind of black, though. More so, without clothes. I changed my bra and changed my skirt for shorts. I fixed my hair and looked at my sleepy eyes and said to myself, Get ready.

When I got out, Akachi was gone.

At the train station, I used the fifteen minutes to pace, flexing my leg muscles, prepping myself. The station was quiet. I saw some mob with Roar shirts and I was sorry I would miss the game as it would be played at the same time as mine. I thought ahead to my game. An unknown quantity, this opposition. They’d won their first game, narrowly. I wondered if my dad would be there. Was he wondering where I was, whether I’d got my application in and how I’d get to the game? He always took me to the games. I had to ride my bike to training quite a lot, but he always took me to the games.

The lit train crunched into the station, and I felt the studs of my boots dig into my back as I put my backpack back on.

Books on this page and more are available from education suppliers, all good bookstores and online from Fremantle Press. Automatic discounts apply for Australian teachers purchasing class sets of 10 or more.