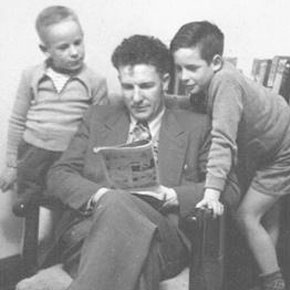

How do you face Father’s Day without your dad? Jon Doust, author of the One Boy’s Journey to Man series, tells a story about his father, Stanley, and the gifts Stan left his sons

I met a bloke last week who said his father died 20 years ago and he had never got over it. My father died in 2002 and I can still hear him telling me how to remove the ceiling fan in the bathroom. I’d done it a couple of times before and I was over 50 years old, but that didn’t make any difference. As far as he was concerned I was still ‘bloody hopeless’.

His funeral was a classic country-town affair. The police stopped the traffic, locals lined the main street and the hearse stalled. When it stopped, about halfway through town, one of my brothers poked my ribs and said, ‘Look out, he’s got one more thing to tell you.’

When Stanley Roy Doust was diagnosed with a malignant melanoma … I was shocked and wept for days. I had to get it over before I saw him. He wouldn’t want any son of his blubbering in his face.

From September to December, my brothers and our wives were with Dad and Mum every week, driving him to chemotherapy, shopping, cooking, cleaning, and caring for Mum.

Dad had been Mum’s full-time carer ever since she broke both hips. She broke one at home, in Bridgetown in the south-west of Western Australia. My brother Jamie said she turned to go back into the kitchen for more food when the hip collapsed and she fell to the floor. He ran to her and she said, ‘I’m okay, dear, you finish your meal.’

Mum broke the other hip in a Bunbury hospital. She tried to leave the bathroom without assistance, turned, and the other hip collapsed: ‘The staff are very busy in here and I didn’t want to bother them.’

That was how they were. They kept saying, ‘We’ll go into a nursing home. We’ll get full-time care. You can’t keep doing this for us.’

He never complained. And he never gave up.

One day we had a working bee at his house in Bridgetown. It was after a particularly heavy bout of chemo and he wasn’t feeling too posh.

There were about 10 of us, weeding, mowing the lawn, collecting garden refuse. We were only five minutes into the job when the back door opened and there was Dad in his work clobber, mouth open and issuing instructions: ‘You can’t get a good cut like that. That hose should run straight. The rubbish goes on that side of the compost heap.’

We knew Christmas would be Dad’s last and we wanted to do something special. The eldest brother came up with a winner: a fishing trip by houseboat, just Dad and his sons. We did it.

Sadly, Dad had a stroke that week and by the time we got him on the boat he was a bit ragged.

We did it again this year: Stan’s four boys and his grandsons. We talked a lot about Dad. He was a leader and a legend in the South West, a stirrer with a great sense of humour, a kind and forgiving man, and no father could have been more generous.

There was only one thing missing. All our lives, Dad had never said he loved us, that he was proud of us, or that he respected us. Never. We knew he did, but he never said it.

Then a family friend called a day before the funeral and said, ‘I have a note for you. From your father.’

It’s a beautiful note. He tells us why he never said those things, that it was hard for men of his generation, and then he says them.

Who would want to get over a man like that? He’s an inspiration. In his darkest hours, he not only found the courage to break through a lifelong pattern of behaviour, but he left his sons with a wonderful gift: his love, his pride, and his respect.

Read an excerpt from Jon’s latest release, Return Ticket, the last book in the One Boy’s Journey to Man trilogy:

The trip down the river was Thomas’ idea, and Bill and I agreed immediately. My brother Thomas didn’t think it through the way I did, and when I asked him he said: I just thought it would be nice.

No underlying agenda? I asked.

Like what?

To bring the family closer together, bang our heads and reopen old scars, or heal festering sores?

You haven’t changed, have you, Jack? Still digging for deeper meanings. You should have been a barrister. You would have been excellent in a courtroom.

Glorvina had wanted me to study law, believed the skills I had lent themselves to it, the analysis of issues, the pitch battles in the courtroom, and she thought I had a thick skin because I seemed to go off and do things without considering the consequences. But she was wrong. Consequences sat heavy in me. I did, however, enjoy a good argument, especially if it finished with both parties recognising the validity of the opposing position. It was like old friends who fought a good fight, would pummel each other to submission, get up, laugh, hug, forgive, and move on. I took a Jungian view in argument. My father said to me, not long before his melanoma diagnosis: You were a cantankerous, argumentative boy.

No I wasn’t, I said.

Yes you were.

No I wasn’t.

Yes you …

Hang on, when you and I argued, what was your objective?

To have you agree with me. That is the purpose of an argument.

It was never mine, Dad. All I ever wanted was for you to accept who I was, that I might hold a different view, sometimes, perhaps, even agreeing with you, but from a different perspective.

He needed to ponder that suggestion and settled back deeper into the chair he had not long got up from. It was one of those chairs popular with older men, with a footrest that moved forward when the occupier pushed back. He sat leaning forward, not quite ready to rise, or to fall back, then lifted his head and stared at me.

You and I both lived in a country at war, he said. We never talked about that, did we? I’m sorry.

To watch a man you have known all your life as a strong, firm man soften before you, then apologise, in particular for an occurrence, event, or slight perceived on reflection, is a moment to savour, and cherish.

War changed us both, Dad, I said. You came home in 1946 and started a family. I came home in 1977 and gave myself some time before starting a family. You gave yourself no time to recover. And I think I’m still recovering.

He lifted himself out of the chair with difficulty and walked towards me, slowly, as though considering his next move.

You want a hug?

I’m not good at it, Jack.

We hugged the hug of the quick and the living. He went back to his chair and I moved into the kitchen. It had become clear to me that as my parents moved through their final weeks, it seemed important for them to reveal long-held secrets. I wondered if I would need that time, later, with my own son.

Boy on a Wire, To The Highlands and Return Ticket are available in all good bookstores and online. You can listen to a podcast about the making of the trilogy here.

Boy on a Wire

Buy the book. [photo]

Read a sample chapter.

Access teaching notes.

To The Highlands

Buy the book. [photo]

Read a sample chapter.

Access book club notes.

Return Ticket

Buy the book. [photo]

Read a sample chapter.

Access book club notes.