A Tale of Two Editors

In which, via a series of plot twists and non sequiturs, a prose editor gets around to asking a poetry editor about how and why she does what she does. Metaphors abound.

It was neither the best of times nor the worst of times. On both sides of the country, people vacillated over whether to put a possessive apostrophe in goats cheese. There on the west side, one kept editing prose, and there on the east side, the other kept editing poetry.

First, some editorial admissions

I have a suspicion that being an editor is just the vocational expression of a certain kind of personality. Editors may find themselves irresistibly drawn to the establishment or restoration of order in other spheres. They may, for instance, derive satisfaction and pleasure from repetitive tasks like checking a child’s head for lice, or sifting for microplastics in the sand during beach clean-ups. They may (as I did) spend time as the most over-qualified and contented filing clerk a law firm has ever seen.

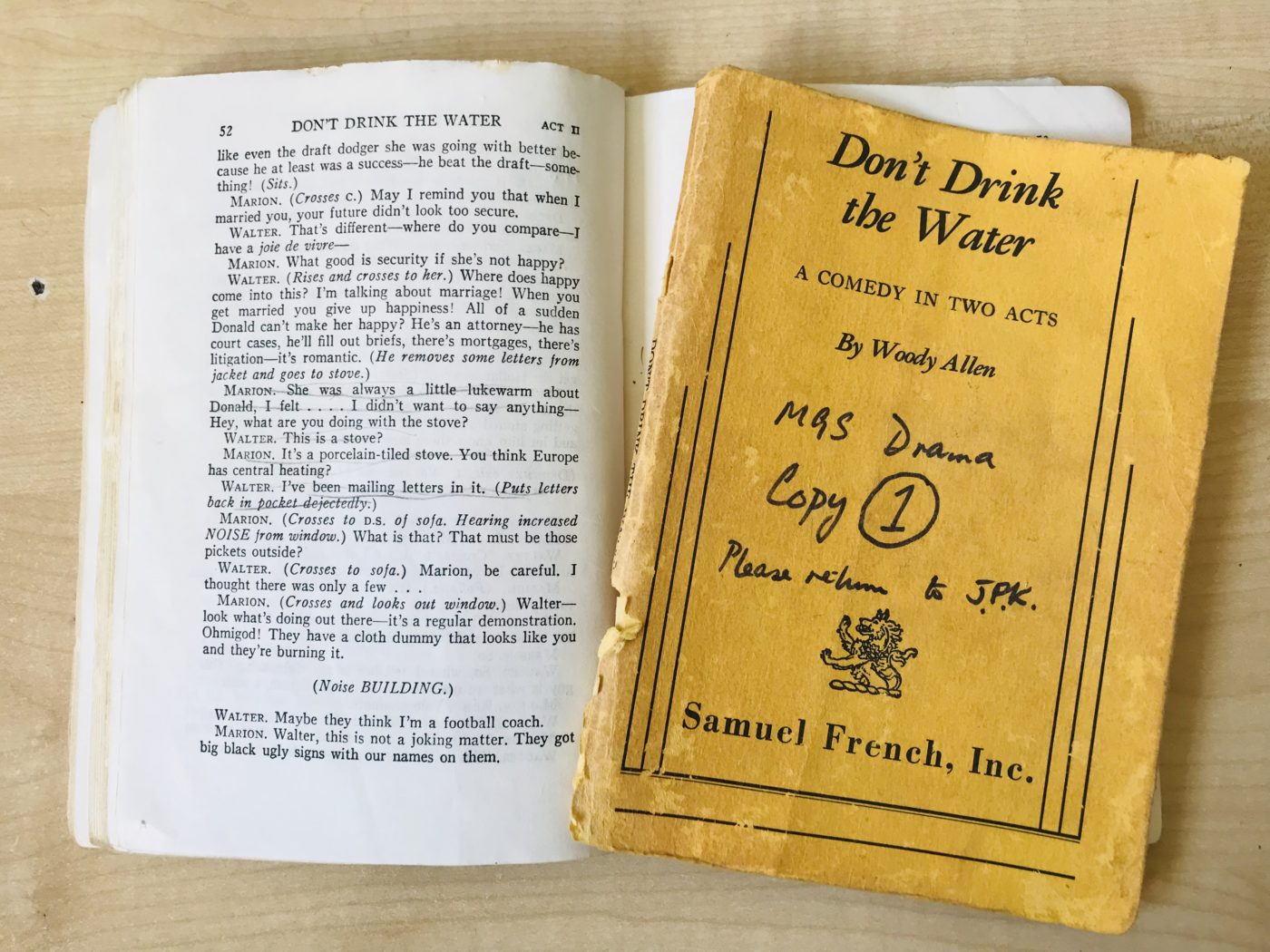

Given my disposition, it was no surprise that I was always the prompt in the school play. Some might say it was an extreme crush on Ben Grant that kept me riveted in the wings, but I like to maintain it was nascent evidence of professional potential: my high-boredom threshold, my ability to look at the same words over and over, my capacity to apply high levels of concentration to the script in a way that felt fresh every time. It was not as if the arresting Ben Grant ever needed me to prompt him – the wings I was waiting in never became the wind beneath his – but being a prompt did lead me to become fluent in Shakespearean English, and to think about the whys and wherefores of the construction of comedy in the writing of Woody Allen, however unfashionable that now may be.

We have a kind of joke in our office that all editors are Librans with Ravenclaw rising. Which is to say that three editors in our office share birthdays between September 26 and 29 – though that is not to suggest that editors cannot be born under different stars (maybe Aquarius, Gemini, Virgo …). Editors are, after all – to strain the metaphor – cosmic chameleons. They are expert at inhabiting the language of others in the service of a manuscript for as long as it takes to make it perfect. The satisfaction of honing a work from rough to smooth is orderly, instinctual and skilful.

The kind of partnership that arises between editor and author can be an intimate experience. At the recent York Writers Festival, one author said to me, ‘I felt as if we should be sharing a cigarette at the end of some of those scenes we worked on together.’ A crime writer, conversely, complained to his wife about my lack of appreciation of his early sex scenes, to which she replied, ‘Join the club.’ (Happily for all, and with a little constructive criticism, his sex scenes have improved.)

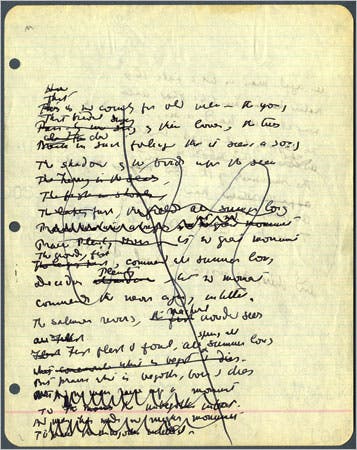

For me, the most intimate experience of all is editing the handwriting of authors. That feels as close to original thoughts as one can get – the raw stuff that moves from the mind of the author to the page. One author and I recently did more than a dozen rounds in hard copy on a novel that had visual elements which had to be made just right. I would print out a fresh manuscript. He would mark it up and send it back. Seeing this author’s handwriting was like watching over his shoulder while he composed. It made me realise how ordinarily we rely on the genteel restraint of typefaces to keep the transaction businesslike, and the roles distinct.

All the editors I know are good-natured, equable people with steady emotional barometers. We are good listeners, attuned to the needs of others. If there is a limit to our goodwill, it takes a long time to reach. The only time this particular chameleon roared was at her father’s funeral.

My childhood ballet teacher had turned up – to pay his respects, or out of idle curiousity. I had not seen him in forty years. He was excited to hear I was a publisher and editor and, when we gathered outside the chapel at the end of the service, he stepped in front of me to tell me all about the poetry collection he had written and to ask if I would read it. He did this while my father’s coffin was being placed in the hearse for its final journey. He stood between me and the hearse, and bludgeoned on, and my dad in his coffin slid away. Any need for social etiquette was expunged. I told the ballet teacher sharply that this was not the time or place. I executed an abrupt pirouette on him in a distinctly uneditorial fashion.

How a poetry editor edits

Most of the editing I do is in the area of prose. But right now in the publishing cycle, we are editing our poetry for release in 2022, and I have been wondering what it is like for poetry editors: the ones who work at the very centre of language’s engine room, right up close to the machine. How do editors edit poetry? Is it different from editing prose? What is the difference if that editor is themselves a poet?

I fall into a phone conversation with my friend, the poet Lisa Gorton, to ask her how she edits. I have known Lisa for thirty years – long before I even knew that editing was a job. The way Lisa inhabits language is perfectly beautiful. I still recall lines of her poetry from when we were in our late teens, and I have carried those scraps of language with me down the years.

As we converse, Lisa several times mentions the importance of reading. And she is right: there are so many kinds of reading an editor needs to be able to do – the brain shifting gears and absorbing text in a different way depending on what is required, though all must look the same from the outside. (Look, there she is, still at her desk. Just reading – who gets to read for a living?!)

‘The first work is to read the manuscript several times, at different times,’ says Lisa, ‘to try to recognise the particular language of the poems. All editorial suggestions need to derive from this awareness of the poet’s particular language – the poet needs to feel that an editor’s suggestions are not attempts to impose a different vision on the work, but attempts to help the poems fulfil the poet’s vision more freely and exactly.’

What is her aim? ‘To make the manuscript more fully itself, and one which is distinctively in the poet’s voice.’ And what is her role? ‘To try to protect poets from accidental misrepresentations of what they are trying to do or say.’

She says that the first edit is structural, but any structural edit needs to reflect this understanding of how the poet’s vision is at work in individual poems. ‘The ideal is for the whole collection to embody, in its structure, the kind of logic that is shaping the poems. What connects the poems, and what separates them? It might be structures of imagery, or tones of voice, or sudden free changes of thought, or crystalline patterns of growth. The logic of the poems can shape the logic of the structure.’

Does Lisa feel that her editorial and poetic selves are alike, and equal expressions of the way she inhabits the world? She tells me that editing is more like reading than it is like writing. It requires the trancelike quality that occurs when we pay close attention to language. And then she offers me the word parallax – seeing an object from two different lines of sight. ‘When I am editing a work and I feel that some part of it isn’t yet what it could be, I feel a sensation like parallax, like seeing something through the surface of water: a kind of doubling of vision, seeing the poem bend away from where it could be. I have the same sensation when I am editing my own writing.’

Lisa edits as she herself likes to be edited: noting every place where she thinks the poems could benefit from more attention, but trusting the poet to judge whether to take up or ignore these interventions: ‘I would be upset if poets ever took my advice against their better judgement.’ She treats every draft as new; she doesn’t check whether the poet has or hasn’t taken any suggestion. Occasionally, she’ll suggest different possible sequences, if only to open up a different sense of possibility for the structure of the collection. While an editor might notice places where a poem falls away from itself, and loses intensity, she feels that the poet is the only one who can transform the work.

‘Some of the best questions I was ever asked by an editor were the simplest,’ Lisa says. ‘Chris Wallace-Crabbe wanted to know, Why do your lines end where they do? And Ivor Indyk asked, Who is ‘we’?’ There are some poets who hate to be edited. The poem, as they perceive it, arrives fully formed, and any editing is a kind of interrogation, something the poet does not feel themselves at liberty to give. ‘I think that Emily Dickinson and William Blake would not have been easy to edit,’ Lisa says. ‘But editing itself can – should – be a creative process.’ She tells me about a moment that changed her life. In a library at Oxford, she encountered, by chance, a book of Yeats’ drafts of some of his poems. His poems began in a fairly conventional song form, but every successive draft became weirder and wilder and more like the Yeats she knows. The revelation for Lisa was that editing could be a way of finding the freedom of the work: ‘The role of an editor is to help poets with this process, to prompt and protect the writer so that the collection is exactly as the writer wants it to be.’

A tale of two editors, cont.

It was the best of times and the worst of times. Some people thought editors got paid to read for a living. Others, that editors were the OH&S officers of their author’s imaginative worlds. And mixed metaphors were still being used to explain life’s mysteries.

After Lisa and I are done, I start to weed the lawn, wondering whether there is a difference between what she does as a poetry editor and what I do as the editor of prose. We both pay heed to the work as a whole and also look at every single word on every single line. But the medium is very different.

I think about editorial decisions I have made recently. In a memoir, the author used the verb enveloped to describe the wicked grip of her attacker’s arms, and also what the wind did to her when she stepped off the plane. It seemed to me that a different verb was needed, because it felt unintentional on the part of the author that one should recall the other.

Another author and I decided that her novel could start in chapter two. The narrator of chapter one need not reveal herself so soon. This way, mystery and suspense will be amplified and there will be some enjoyable work left for the reader to do.

In another manuscript, I have been looking up flight schedules and in-flight menus, and whether there is any difference between the words arrgh and argh. (There is.)

In some areas of my life, I have been described (justifiably) as being overinvolved. But in the arena of editing, attending to the minutiae can be helpful – and involvement is not over until editor and author step back together and say, ‘It is done.’

So what does this Libran Ravenclaw think as she pulls weeds from the garden? That an editor’s role is to be in service of others and to be in service of language. To listen and respond. To ask questions and to honour the answer. To be invisible in the work’s final iteration. Editors may be cosmic chameleons – but we are pernickety, obsessive, intuitive chameleons with multiple lines of sight; we flow through the galaxy of language like water.