Past and Possibility: The Fertile Estuary of History, Historical Fiction and Speculative Biography

On a morning exploding with pigeons, I fall into a phone conversation with my old friend Kiera as I walk to work.

‘Can we talk about historical fiction?’ I ask.

‘I don’t write historical fiction,’ she says. ‘I write speculative biography.’

Isn’t that the way of writerly research, I think with a sigh: you push out your little boat in a certain direction, clutching your map, and moments later find yourself spun around? But then I look at the diamonds from overnight sprinklers still sparkling in the grass and think how I have never had a conversation with Kiera in which I did not learn something.

I say, ‘Can we talk about you as a writer of speculative biography?’

‘Of course,’ Kiera says, as the pigeons settle hopefully on the rooftops, and I pause on the oval to chat with her in the early sun.

Kiera Lindsey is a writer with a PhD in History. She now holds the role as South Australia’s History Advocate. In recent years, she has written a speculative biography called The Convict’s Daughter: The Scandal That Shocked a Colony, about the life of her great-great-great-aunt Mary Ann Gill. Her second work, Wild Love, about the Australian artist Adelaide Ironside (1831–1867), is being prepared for print. What Kiera has done in writing these speculative biographies is combine historical research with fictional techniques to create a work that is ‘factually informed but imaginatively conceived’.

So, what is the difference between Kiera’s work and most traditional historical biographies? According to her, while the historian aims to be exhaustive in their endeavours, the writer of speculative biography uses narrative techniques to be evocative in theirs: they draw on a mode of delivery, and compelling characters whose actions are true, using the devices of scene, setting and dialogue to drive narrative momentum. Kiera says:

‘If the historian tasks themselves with explaining the iceberg beneath the water, then the writer of speculative biography describes the iceberg’s tip in a way that ignites the reader’s imagination about all that lies beneath … In my work I am always trying to achieve a delicate balance between the two.’

What, then, is the difference between her work and a novel? In writing history ‘that tastes like fiction’, her work holds up to factual interrogation because it is built on fact, though the space in which she works is truly one of speculation and involves narrative and fictional techniques. Such work takes time and enormous effort. The Convict’s Daughter was based on the four years or so it took Kiera to conduct her PhD in history, plus another two years of research while writing the book under contract. It has taken seven years to write the work on Adelaide Ironside and involved visiting more than fifty archival holdings in Australia, Italy and throughout England, Wales and Scotland.

‘In concentrating on actual figures from history and trying to make sense of gaps in the archive where it is difficult to determine what these people did, I am always trying to advance what is most probable.’ Her emerging narrative is the way she tests a hypothesis ‘after triangulating all the available evidence – ranging from an official record to a piece of artwork, a fragment from a letter, engravings on jewellery, retracing the steps of characters, or botanical drawings which might provide some indication of when someone could have walked along a certain cliff top at a certain time of year.’

Using narrative to test her speculations, Kiera often finds that when a narrative falters and has to be redirected, it is because her hypothesis doesn’t work. Narrative success, conversely, serves as confirmation that the speculation she has been experimenting with is sufficiently reasonable to allow the story to progress.

The ultimate test comes when the work is put to the reader. And here her editor, Elizabeth Weiss, acts as an advance party, keeping an eye on narrative momentum by asking: What does the reader want at this moment? What is working and what isn’t? What is surplus to this story?

As a writer of speculative biography, Kiera stands somewhere between historian and novelist. It is a space for her that is full of potential: ‘What happens when – rather than keeping these two ways of knowing on either side of the ravine – we think of history and fiction as streams which intermingle in a fertile estuary and allow new forms of writing the past to flourish?’

I believe that there are many deltas in this ‘fertile estuary’: much of what Kiera says chimes with my experience of working with writers whose narratives are set in past times and real places. I think of Leigh Straw, a historian who is also drawn to story as a way of sharing history. In The Ballroom Murder, she assembles for the reader all the court records and newspaper reports of the day, as they describe the point-blank shooting by Audrey Jacob of her former fiancé, Cyril Gidley. This shocking event took place in August 1925 in front of hundreds of witnesses at a charity ball in Perth’s Government House. The murder trial was open-and-shut, until suddenly it wasn’t, as Jacob’s defence counsel expertly played to both press and jury. What made the jurors deliver the verdict that they did? Straw presents all the available evidence in a beautifully woven narrative, leaving the reader to answer that question for themselves.

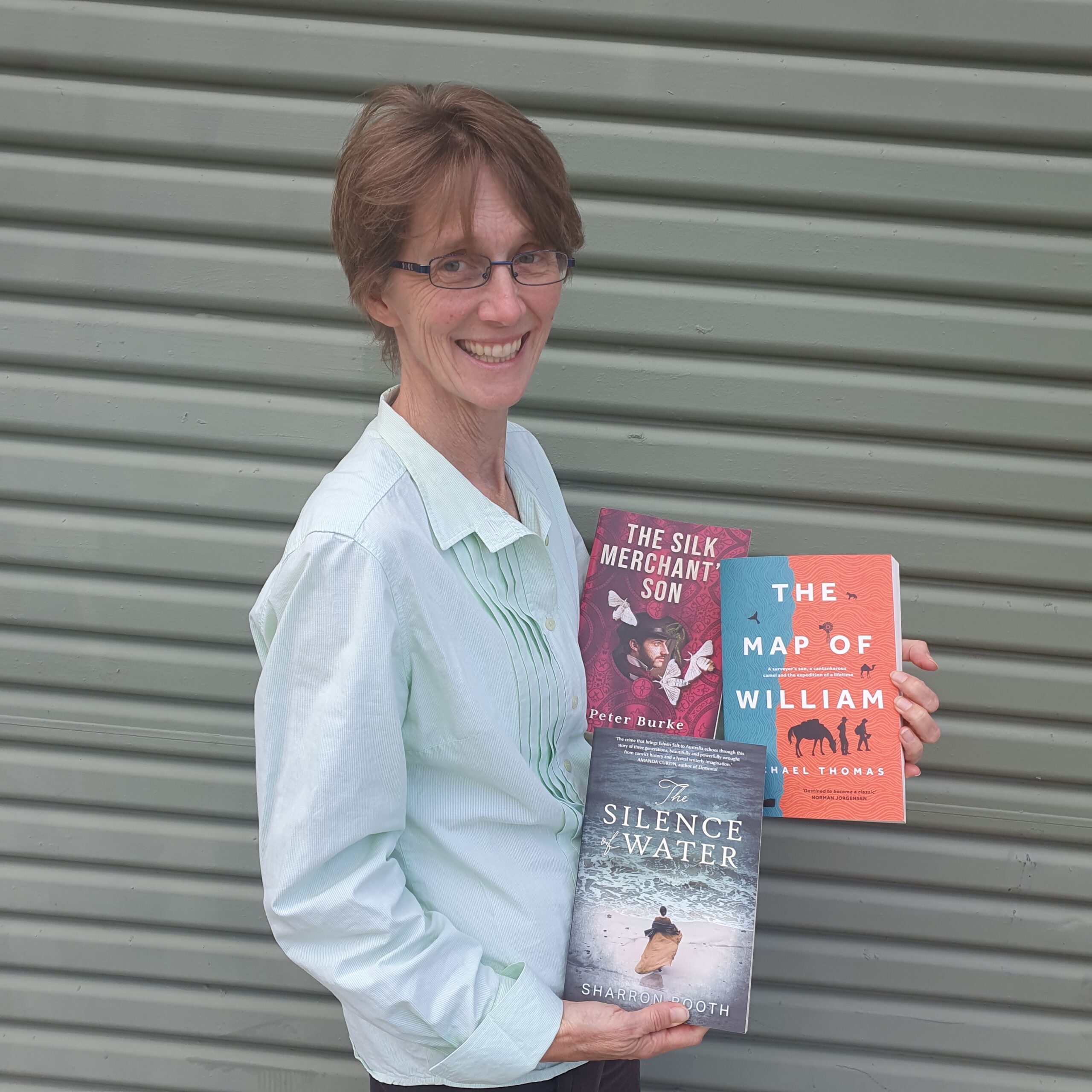

In earlier research into brothel madams like Madam Marie Monnier, and underworld figure Kate Leigh, Leigh Straw has sought out stories that are often overlooked in history. Some subjects may be manifestly visible as Audrey Jacob was; others may have left only faint traces of their lives by dint of class, cultural origin or gender. As author Sharron Booth found during her research for the historical fiction novel that was to become The Silence of Water, ‘some kinds of people were either heavily classified and controlled via colonial archives or ignored completely. Some were written about in ways that dehumanised, demonised or marginalised them, reflecting the biases, exclusions and power structures of the era’.

By retelling such stories, writers of speculative biography and of historical fiction can address the imbalance of historical records, which are typically made by men for men. Kiera says: ‘When I use experimentation and fictional techniques, I do so because I believe that the ends justify my means because they allow me to address the injustice of these archives and ‘re-present’ people who lacked the education, influence and economics to leave much of an archive. The term ‘re-present’ was first coined by historian Greg Dening to acknowledge that such acts are ‘re-presentative’; that is, they re-present a set of possibilities but not the only possibility about the past.’

Whatever the genre, both Kiera and I agree it is important for the writer to find a way to ‘show their workings’ to their readers. Author notes which support the text are one way for a writer to declare their own connection to the material, and to provide an account of their research journey.

This ‘re-presentation’ brings with it a sense of responsibility. While editing, I have found that the sense of obligation continues down the line as I work with the awareness that we are both custodians of the stories of subjects who can no longer speak for themselves.

In The Silence of Water, Sharron Booth felt a kind of moral imperative to retell the story of Mary-Ann Hall. Her research during her PhD led to a novel based on the life of Hall, Hall’s husband Edwin Salt and his descendants, following the commutation of Edwin’s death sentence to transportation. He arrived in Western Australia in 1861. Part of Booth’s challenge was to ‘re-present’ a whole and dignified life for Hall based on the documents that were created after her untimely death. Booth’s research included ‘genealogical records; case documents from the National Archives in London and the National Records of Scotland; people, prison and colonial government records from the State Records Office of Western Australia; along with rate books, newspapers’ and much more.

In the course of revising her novel at Fremantle Press, Sharron recast the manuscript to give Edwin Salt’s granddaughter Fan carriage of the story in a way that emphasised how one individual’s actions can ricochet through decades, and how families can take generations to heal.

As he researched The Sawdust House, David Whish-Wilson walked the streets of County Cork and the hills of San Francisco. He talked to blokes in pubs where stories of Yankee Sullivan have persisted long in popular memory: in the US you can still buy t-shirts displaying the face of the father of modern American boxing.

David had encountered Sullivan off and on during his research for his historical fiction novel The Coves, but it wasn’t till he read an account by Sullivan’s widow of her husband’s melancholia that the spark caught. David is no stranger to writing non-fiction. His lyrical non-fiction work Perth, in the NewSouth City Series, was built on the foundation of his own question: Why is Perth the way it is? But historical fiction allowed David to move into the space where there were as many absences as presences:

‘As a younger writer, I was very influenced by friend and mentor Kim Scott’s early approach of using fiction to write into gaps in the historical record. I’m looking at gaps in a very different kind of history, but the approach is something that is useful, aiming to use the persuasive and immersive tools of fiction to fill out a picture that contains plenty of silences. Fiction, in its paradoxical way, can certainly feel like the truth, and by way of condensing and reordering, it can also be truthful to the historical record.’

David’s research began with him poring over Old Bailey court records online. Later, in Cork, he was shown the birth certificate of Sullivan, where it is kept in a shoebox by a historical society. In San Francisco, he touched the prison walls where Sullivan lived out his final days in 1856, incarcerated by the Committee of Vigilance.

What hard evidence he found on Yankee Sullivan was tantalising, and like Kiera, David tested it all to see which narrative held as he wrote into the spaces in between. Elsewhere, literary scholar Donna Lee Brien has described this process beautifully: ‘The facts formed a line of buoys in the sea of my own imagination’.

Editing David’s novel was one of the most absorbing editing–writing partnerships I have ever participated in, not least because we worked to ensure that the form of the book echoed the content. The dialogue between Sullivan and the Mormon journalist Thomas Crane starts at a new page for each new speaker. As with poetry, the blank spaces around the words help to shape the reader’s experience. Such pauses in the work are part of the ebb and flow of conversation as Sullivan’s memories, spoken aloud to Thomas Crane, breach the prison walls.

Some stories drawn from history are more familiar to a reader than others. I first read the manuscript of Portland Jones’ Only Birds Above as I waited outside a changeroom in a shopping centre. Portland lives and works with horses, and this intimate knowledge can be felt on every page. Only Birds Above is an account of the lives of men and horses and war. Perhaps the test of any writer in this well-trod arena is how their story will deliver the tragic ending of Western Australia’s 10th Light Horse Regiment. In that clothing store, I read Portland’s manuscript and wept.

There is another such scene in Michael Burrows’ Where the Line Breaks, when the men of the regiment are told their horses can’t come home. In the right hands, a well-worn story from the past flings the reader back so vividly, it can be almost unbearable.

As Western Australia approaches the two-hundred-year mark of colonial invasion, it is not surprising to find convict and early settlement themes appearing often in the historical fiction being submitted to Fremantle Press, and they can be a frame for some writers to think about their own origin stories. Michael Thomas writes that: ‘… the inspiration for writing The Map of William was an article I read in The Cardiff and Merthyr Guardian, 4 March 1848, headlined “The Murder in Whitmore-Lane, Cardiff”. Three columns of the broadsheet newspaper were devoted to the trial of Alexander Thomas, my great-great-grandfather. In the court transcripts he was referred to as Alec the Devil, a notorious member of a gang of pimps and murderers. Alexander should have been sent to the gallows for kicking a man to death but miraculously escaped the hangman’s noose. Instead, at the age of twenty-two, he was transported to Western Australia to serve fifteen years for manslaughter … If not for Alexander, I would have remained unaware of this period in our history. His journey from the streets of Cardiff to Old Fremantle and further north to the Murchison, Pilbara and Kimberley regions of Western Australia was typical of so many convicts and no more or less remarkable.’

Michael’s novel is set in 1909 and was inspired by his research into the life and times of his notorious forebear. In The Map of William, the eponymous boy travels north with his father to map water sources in the Pilbara. Michael Thomas has a deft touch when it comes to writing about men who commit dark deeds, or heroic ones. An unworldly fifteen-year-old boy can be the perfect foil to take the reader back in time precisely because his eyes are still open to injustice and human failings and bigotry. While historians may counsel against first-person narrative, Kiera sees great potential in such stories, to ‘return the reader to a sense of the past where all is still contingent. When we stand in the shoes of a character and at a crucial crossroad where they have to make difficult decisions, we gain a potent sense of how challenging life can be and we become more empathetic. First-person narratives can deepen our understanding of both the past and ourselves.’ And so, the world unfolds before William at the same time as it unfolds before us.

As I followed the footsteps of the author, who was following William in his footsteps, Michael and I periodically paused to think about the things that William was witness to – and to asked that important question: who is speaking for whom? Along the route, William is appalled by the common signs of Aboriginal men and women in neck and ankle chains. Michael had to write such scenes and others, very carefully, and to think what language he would use to describe what William saw.

When working in an ancient place with a deep cultural history that is not mine and is often not my author’s either, and when writing in the same space occupied by the original invaders, it becomes apparent that responsibilities with historical narrative exist at every level. Every sentence should be navigated with care. Does a particular word need to be used or a scene portrayed, even if both are historically ‘true’? Does such usage perpetuate uneven power play? What will readers tolerate in the name of historical ‘accuracy’ – and what is no longer tolerable?

An ‘annoying young man by the name of Fabrice Cleriquot’ is the chief protagonist in The Silk Merchant’s Son. Fabrice is a professor of linguistics, hurriedly dispatched from Lyon to Australia with a quantity of silkworms before he can bring further disgrace upon his family. He joins twenty-six missionaries from Spain, France, Ireland, England and Rome, aboard the Elizabeth and they arrive in 1846 in the Swan River Colony fired with the mission of saving the ‘poor souls’ living there. Without a second thought, little Noongar girls playing in the bush are plucked up by the Irish Sisters of Mercy and taken to the convent to be raised without their parents as ‘good Christians’. With casual ease, Bishop John Brady takes out his pen to divide the continent into three vicariates to be administered by the Roman Catholic Church.

Burke’s is, at heart, a story about ‘mutual miscomprehension’: ‘The Catholic missionaries had trouble enough communicating with one other, having seven different native tongues plus Latin, but not one of them spoke the language of the people they had set themselves to convert; not even Bishop Brady, despite the Noongar–English dictionary published in Rome in his name. In this story we have a French linguist trying to understand the spoken Noongar word, and mostly failing; hearing, for example, gouljacque in place of kooldjak for the black swan, or coumarle for koomal, the possum.’

‘Mutual miscomprehension’ is a term wryly deployed to characterise encounters which, for the original inhabitants of this place, precipitated decades of devastation. Fabrice the linguistics professor is a useful vehicle for this story but the others who populate it, and who cause so much damage, were very real. It is Burke’s lightness of touch, and his insistence on his characters seeing the world only through their own eyes, that allows him to convey for the reader the dreadful irony of their missionary zeal.

Numerous manuscripts based in history are submitted to Fremantle Press every year. Often the research is solid, and the idea for the story fine, but often, too, something about the manuscript fails to ignite. Has the writer been unable to find a compelling way to work within the constraints of their subject matter? Are the facts which the author has drawn on too scant to construct an engaging narrative or are they too heavily deployed? Though the research process must be exhaustive, Kiera says, the narrative should not, as her editor puts it, be ‘irritatingly obvious’.

Whether one is using narrative techniques to parse available facts, or facts to deliver the ‘truths of fiction’, the ultimate skill of purveyors of history is perhaps not to make us feel as if the past has come to us but rather as if we have been taken back there.

What strange alchemy is it that makes us trust a storyteller, that allows a little history to lodge inside us? It is a marvellous thing.

For now, the workday calls, and it is time for me to leave the shining grass. Pigeons take flight from the crest of the roof as Kiera and I bid each other farewell.

We are all floating somewhere on this fertile estuary, I think, as the line between us disconnects. Each compelled to understand the world, drawn to stories via a button of bone, a slouch hat, a shoebox treasure, the fragments of lives gone before but somehow still present and waiting to be found.

REFERENCES

Kiera Lindsey, South Australia’s History Advocate: www.history.sa.gov.au/south-australias-history-advocate.

Kiera Lindsey, The Convict’s Daughter: The Scandal That Shocked a Colony, Allen & Unwin, 2016.

Kiera Lindsey, Wild Love (working title), Allen & Unwin, 2023.

‘factually informed’: Anna Haebich, ‘Somewhere between fiction and non-fiction: New approaches to writing crime histories’, TEXT Special Issue Website Series 28: Fictional Histories and Historian Fictions: Writing History in the Twenty-first Century, eds Camilla Nelson and Christine de Matos, April 2015, www.textjournal.com.au/speciss/issue28/Haebich.pdf.

‘speculative biography uses narrative techniques’: Donna Lee Brien and Kiera Lindsey, eds. Speculative Biography: Experiments, Opportunities and Provocations, Routledge, London, 2022. For more see: www.auswhn.org.au/blog/speculating-fragments-informing-imagination.

Leigh Straw, The Ballroom Murder, Fremantle Press, 2022.

Leigh Straw, The Petticoat Parade: Madam Monnier and the Roe Street Brothels, Fremantle Press, 2021.

Leigh Straw, The Worst Woman in Sydney: The Life and Crimes of Kate Leigh, NewSouth Books, 2016.

‘some kinds of people’: Sharron Booth, author note, The Silence of Water, Fremantle Press, 2022, p. 229.

Greg Dening, Performances, The University of Chicago Press, 1996, p. 37.

‘genealogical records’: Sharron Booth, author note, The Silence of Water, Fremantle Press, 2022, p. 227.

David Whish-Wilson, Perth, NewSouth, 2020.

David Whish-Wilson, The Sawdust House bookclub notes, fremantlepress.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/BCN_THE-SAWDUST-HOUSE.pdf.

Donna Lee Brien, “‘The facts formed a line of buoys in the sea of my own imagination”: History, fiction and speculative biography’, TEXT Special Issue Website Series 28, www.textjournal.com.au/speciss/issue28/Brien.pdf

Portland Jones, Only Birds Above, Fremantle Press, 2022.

Michael Burrows, Where the Line Breaks, Fremantle Press, 2021.

‘the inspiration’: Michael Thomas, author note, The Map of William, Fremantle Press, 2023, p. 277.

‘an annoying young man’: Peter Burke, The Silk Merchant’s Son, Fremantle Press 2023, p.13

‘muutal miscomprehension’: Peter Burke, ‘Before the story starts’, The Silk Merchant’s Son, Fremantle Press 2023, p. 11.