Hear ye, hear ye! Go behind the scenes of Agincourt with the author of Nock Loose, Patrick Marlborough

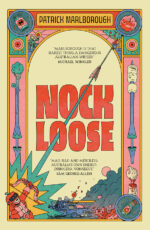

Shortlisted for the 2023 Fogarty Literary Award, Nock Loose is Patrick Marlborough’s screwball comedy revenge thriller, centred on a small Australian town that takes its annual medieval festival very seriously. In this interview, Patrick tells us how their novel – and chaotic characters – became into existence.

Where did the idea of Agincourt come from?

In 2016, I attended the Balingup Medieval Festival. I was covering it for Vice. I was struck by the comical anachronisms, specifically the mashup of medieval, nerd, and small bush-town culture. I took a lot of photos highlighting these ironic juxtapositions: guys in plate armour with Monster Energy caps smoking darts, knights wearing speed dealers, washer women playing games on their iPads. Yet when I began thinking about what became Nock Loose, I really just had ‘revenge thriller starring Magda Szubanski set in a (normal enough) medieval festival in the bush’. All my novels are ‘improvised’ but. Agincourt came to me as I was writing the first chapter, which was when I realised I was incapable of writing anything other than a piss-take. With that in mind, Agincourt is really a satire of Australian mythmaking—how we retell our colonial past to fit a very banal, in my eyes very mediocre, present.

Is it the characters or the festival itself that you used to drive the story?

It is hard for me to discuss my process without giving away the game. The version you’re reading is a much tidier, more ‘consistent,’ plot holes filled-in (kinda, hopefully, haha) version of the first draft—but otherwise what’s there is what was there in that first Fogarty shortlisted run. I wrote (that version of) Nock Loose in 2 weeks, writing 12–14 hours a day in a little studio. I plan no characters, plot, setting, dialogue, or theme. They just appear to me as naturally as the mug of tea I’m looking at now. That said, I think my characters manipulate me. Take Conway for instance: in my first conception, he was a much more loathsome, unforgivable, abusive bastard. But he got to chatting to me, and convinced me otherwise—he is a rake and a charmer and yes, a dud, but ultimately, he’s trying. Arthur, too, was originally the book’s Big Bad. But I found his dry wit so enticing that he slowly became its secret hero. Pucker Puck began as a throwaway gag, then became the key to unlocking the book’s secrets (reread it, haha). These people all arrived fully formed—if they change in the writing it’s because they correct my initial perceptions of them. There’s too many examples of this in Nock Loose to list.

In a lot of ways, The Captain took the book from me. He appeared as soon as I began writing about what Agincourt ‘was’, exactly. His stupid sets the tone, haha.

In terms of the festival, it allowed me structure to do what I love best: create meta-histories and parallel fictions. It’s a joke vehicle, and an alt-universe builder. The key to Agincourt—a trap I laid for nitpicking nerds and pedants, really—is that it’s inconsistent. Even the people who live and breathe it can’t really settle on the ‘rules’, or its origins, or what it means exactly. Remind you of anywhere?

Which character did you enjoy writing most?

Ok, I’ll try not to ramble, but ultimately, Conway. I love a liar. I love a deadbeat. I love a grifter who never learns his lesson—someone who cannot help themselves. There is too much of my worst self in Conway, but his energy, his language, his duality—I have bipolar, so make of that what you will—is all very fun to try to get a hold on. As I said above, the book dictates me, not the other way around. Conway literally led me by the nose down a version of his story that maybe isn’t even true—who am I to say?

But! I loved writing Arthur also, because it’s always fun to write a straight man. He is the only Bodkinite who sees Agincourt in its awful totality, yet his cynicism and indifference (at least his performance of it) ultimately binds him to it. He is very loosely based on Paul Keating’s appearances on The 7.30 Report in the 2000s, where he loved to bitch about everything and everyone, while still being a fool for the system that doomed him.

But! If I’m being totally honest, my favourite characters to write in Nock Loose were the Bodkinites themselves. Having the town operate as a ping-ponging chorus of whiney psychos was/is very fun. They bring the world to life, maybe begrudgingly, but it’s all they know how to do.

That said! I love the twins. They arrived very whole and organically. Constable Rinds was originally a villain, but he won me over by being a dag. The Panzers/Coyotes felt like they’d already existed, and do appear in my other novels. Big Ron—who seems to be everyone’s favourite—is heavily based on a man who has been our family friend for literally 75 years; he is a loving tribute to him.

I am a huge nerd for minor characters in fiction (Stubb in Moby Dick, Simon (Stephen’s father) Daedalus in Ulysses, Gamling). The texts (especially Lord of the Rings and A Song of Ice and Fire) that Nock Loose is drawing from/satirising are full of them, so this book is too. Woody Barr and Bill Chuffed (can you tell I was raised in a household where Ben Chiffley is considered a minor deity?) are good examples.

Pucker Puck (PUCKER PUCK!) is me in 40 years, sadly.

This novel is both very graphic and very entertaining. As a stand-up comic, did you bring your understanding from that world into your writing when it came to thinking about how to grab the attention of readers?

There is little separation between my fiction, my comedy, my music, my non-fic/journalism, etc. in my mind. Being capital F ‘Funny’—not New Yorker or Chaser or Leuing ‘funny’—is a cardinal sin in Australian literature/art, which is why it’s so lifeless, for the most part. We are a very humourless, self-serious people, despite somehow convincing ourselves otherwise (much like Yanks think they love ‘freedom’, when they essentially loathe it).

One thing I can’t stand as a comedian is boring my audience. My live shows are complex, confronting, nasty, and challenging—-but you will never be bored, and you will laugh. It’s a guarantee I try to bring to my novels. I am a top-shelf impressionist and improviser—these two knacks probably define/fuel my fiction more than any others.

I do think it’s rather shameful how dull most Australian fiction dares to be. I like slow, difficult, plotless novels (believe it or not). But what I’m talking about is the ‘Stan Original’ vein of Australian writing that makes me feel like I’m reading hallmark cards in a children’s oncology ward. Just die already, it’s sunny outside, I wanna have fun!

I think what a lot of writers and comedians forget, or unlearn, or have hammered out of them by our desperately conservative and cowardly arts industry, is this: you can do and say anything. They can’t stop ya. Go hog wild!

What is next for Patrick Marlborough?

Long-term underemployment.

Beyond that, I am sitting on 4 finished novels: A Horse Held at Gunpoint (shortlisted for The Fogarty Literary Award in 2021, probably the best), Craigie: A Reckoning (which I wrote with the intention to self-publish; it’s very funny but quite evil), FIFO Bebop (retelling of Dante’s Inferno, but about an older FIFO taking a younger FIFO out for a hellish night on the town at the peak of Perth’s mining boom), and Wagger Champloo (4 schoolboys wag school to enter a video game contest in 2002, my assault on the Howard years). I have 20 more planned, 5 more begun, and could sit writing a novel a month if life and this turgid industry would just get out of my way/stop bumming me out so much/forward me a loan.

My plan is to start my own small press that publishes exciting Australian literature, that is literature that isn’t bound to the middle-brow tastes of creative writing program coordinators, state-funded writer orgs (notice how none of these guys ever publish anything? weird!), and donors with the politics and morals of German expats living in Argentina in the 1970s.

But I’m poor and autistic and kinda rude, so it’s a struggle (this biz loves a suckhole, and I am tragically neurologically incapable). If you’re reading this and you’re rich, please send me money. Despite what I said above, I don’t care if you’re evil if your money does good.

Until then, I am and have been for almost 20 years, a working writer. My stuff is all over. It’ll continue to be all over. There will be more live shows, books, albums, and articles, unless Trump ups the cost of my meds by 300%. Then you might see me standing at the intersection with my pants around my ankles, holding up a sign that reads ‘will let you call me the next Tim Winton for $50’.

However, I prefer the path of The Buggerin’ Bandit when it comes to supporting the arts: your money, or your life!

Nock Loose is available from all good bookstores and online.