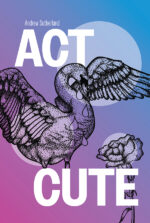

The cuteness aesthetic: Interview with poet Andrew Sutherland

Whether you are searching through handwritten scraps or rediscovering travel journals, compiling a collection of poems can be a difficult but inspiring activity. In this behind-the-scenes interview, poet and performer Andrew Sutherland takes us through how Act Cute, his latest poetry collection with Fremantle Press, came to life.

Can you tell me about the notion behind ‘act cute’? When did the poems you were writing start to coalesce around this idea?

Cultural theorist Sianne Ngai unpacks the aesthetic and production of cuteness as one of the defining aesthetics mapped onto twentieth-century capitalism [Our Aesthetic Categories: Zany, Cute, Interesting, Harvard University Press, 2012]. As an affective aesthetic, cuteness proliferates endlessly; look around and it is everywhere; the more blob-like, big-eyed and harmless it appears, the more it makes demands on us. Purchase me, hold me, squeeze me, purchase another and another me. It is also a ‘minor’ aesthetic: cuteness, after all, is not the same as the beautiful or the sublime. When I was in my early twenties, I was often called ‘cute’ when I wanted to be ‘handsome’. It is (or can be) perceived as a slight, a diminishment, a put-down. The phrase ‘act cute’, I personally associate with Singlish and Singapore, although it has a broader usage and cultural etymology. This idea, I think, is generally always a negative, as in, by ‘acting’ cute it’s implied you are failing to ‘be’ cute. So it is a double-failure: if, as Ngai writes, the aesthetic of cuteness already appears to be failing to make its political or affective demands, to act cute is also to fail to embody or perform oneself (oneself-as-cute) seamlessly. I think I wanted to organise this poetry collection and its game-play with that sense of self – its sincerity and insincerity, its romanticism and disappointment, the disjoint between nostalgia and present tense, the actor and the failed-to-act – through the lens of that (oddly satisfying) double failure. It is a mode that I’m interested in.

Can you tell us about your creative process when it comes to writing a poem? Do you always know what you want to say before you begin? How do you work to refine it? What difference can an editor make?

For this collection, it was more or less my intention to work into a structure, but this doesn’t always eventuate as you map it out. But it is helpful to find the concept of the poem and then find the material, whether that is drafting new or recuperating from scraps, journal entries, memories. Having said that, concept evolves as you write into it.

The third section of this book, “twink death in Europa!!” did start, effectively, as travel journal. I drafted one to three poems every day over a month in Germany and Czechia, and this was very helpful both for having an organising focus and for being outside of my regular environments.

Refinement, repair, the decision to fix or to cut is both the most frustrating and most satisfying part. I want to do that personal rigour before going to an editor. But having an editor is incredibly useful, particularly when trying to consider a collection as a whole. Sometimes it is to test meaning or impact, sometimes it is because their work is to help direct you to your blind spots.

Is there a poem in here that took you by surprise?

Sometimes material will stay in fragmented form for years, and it is surprising and incredibly fulfilling to return to an old journal and realise a phrase or ‘scene’ you had written years ago is exactly what is required.

Do you keep in mind how readers might receive your work when you are writing?

I think there are three overlapping circles of attention to the way I write (these) poems, and this is very much due to the conceits of voice, performativity, address and audience that underpin this book in particular. The smallest and most controllable circle of attention is for myself: is this adequately communicating my intentions back to myself, is it transforming affect, imagination or memory into language in a way that surprises and speaks to me as its author? The second is the specific reader: the addressee, as a range of these poems are in direct address. So the reader in mind is hyper-specific; in fact, an individual. For the poems addressed to Morwenna and to 联, this also meant that these two people helped to comment and shape the poems in draft form, because for these two relationships in particular, the ethics of publishing poems addressed to them meant, to me, that they should be included in the drafting as conversation. But this second circle of attention (the direct address) is heavily mediated by the third circle of attention, which is the imagined audience, who also have to understand or access the poems in some way as bystander, be they eavesdropper or knowing and gathered audience.

Is this a very wanky answer? In short, yes I care what you think of my poems, but not too much 😊

What’s next for Andrew Sutherland?

I will read poems at your wedding for a very competitive fee.

Act Cute is available from all good bookstores and online.