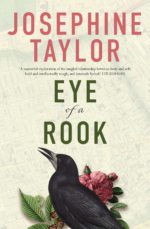

Fremantle Press author Josephine Taylor shares how she made the leap from life to fiction when writing about vulvodynia

A few short weeks after the release of her first novel, Eye of a Rook, Josephine Taylor paused to reflect on her path to publication.

When you develop a disorder that up-ends your life, tipping out all you’ve known and leaving you hollow and stranded, the first impulse for a writer is to write memoir. But it took some years for me to reach even that point.

Why? Well, here’s how the disorder began, so you might understand why it took years to form words around it; why it took 21 years to bring a novel formed from it into the world.

Garden-variety

It began with a garden-variety urinary tract infection in 2000, three months into a new relationship. It continued with unrelenting vulvar pain that mystified all the health practitioners I consulted between March and August – six GPs, two sexual health specialists, one gynaecologist, one naturopath and one doctor of Chinese medicine. Twenty-five appointments and no answers that could account for symptoms that were now made even worse through the sitting to drive to appointments, the invasive hands and implements, the creams I’d been instructed to apply.

Then, in August, I saw a specialist who knew something about the unaccountable raw, burning ache that now consumed my genitals. I found out I wasn’t the only woman with this kind of pain, though it seemed mine was at the more extreme end of the scale. ‘Vulvar vestibulitis’, she said, but for all her knowledge, she couldn’t make it better either.

Slowly, slowly, I began my own research into what I knew now as vulvodynia (pain or discomfort in the vulva for which there’s no identifiable cause and which lasts at least three months). Propped on my horseshoe-shaped cushion, I pored over the internet and medical journals at King Edward Memorial Hospital, then finally met other women who suffered in similar ways and learned from their knowledge.

Investigative Memoir

Words had claimed me. I began a PhD in 2007, following the thread of this pain back to Ancient Egypt and Ancient Greece and immersing myself in the trajectory of hysteria – a history that situated this pain in a larger narrative formed, driven and written by men. I discovered a rich confluence of ideas and treatments in nineteenth-century England and Europe, ranging from the barbaric surgery inflicted on women with so-called hysteria by Isaac Baker Brown, to the sympathetic and accurate description of vulvar pain by early gynaecologists and nerve doctors. I watched the ideas of Sigmund Freud bubble down into distorted versions in psychiatry and gynaecology, manifesting in a psychoanalytic interpretation of vulvodynia, encouraging experts to see such disorder as based in unconscious psychological conflict: ‘all in your head’. I observed the onus landing on the woman herself rather than on medical knowledge. I explored alternative ways in which we might understand the pain.

My investigative memoir was complete. Vulvodynia and Autoethnography won several research awards and sparked interest in publishers, but it was a 100,000-word unwieldly beast of a thing, and ultimately seemed to be too much for a publisher to contemplate taking on.

That Hand

I published personal essays drawn from my PhD thesis, but it wasn’t enough. Something heavy and demanding still pressed at me: I needed this material to impact the world and to make a difference for the millions of women living with versions of this disorder.

I hadn’t written fiction before, but Susan Midalia, who was to become my writing mentor, suggested of an essay I’d sent her for an assessment, ‘The other possibility is to rework this scholarly material into fiction’. Her confidence in that capacity must have stayed with me, because all it took was to be in a writing workshop with a good enough prompt and a scene sprang to life: a Victorian man called Arthur Rochdale consults surgeon Isaac Baker Brown about his wife’s inexplicable private pain. This scene became my short story ‘That Hand’, which was published in the anthology Other Voices.

Silk Purse

It was 2013, and I was off and racing!

The characters in my story – Arthur, Isaac, Alice and Duncan – quickly began to form their own lives and I knew almost immediately the structure needed for them: a contemporary woman with vulvodynia carries out research to make sense of her disorder; a man in Victorian England seeks help for his wife with the same pain; the narratives weave together and are connected in a way that the reader only discovers later in the book.

I called my novel Silk Purse, because it is the perfect metaphor for the female anatomy. I brought a silk purse into the lives of both Alice in Perth and Emily (Arthur’s wife) in Victorian England but, over time, the metaphor began to feel too obvious and explicit. It also felt to close to me, the writer. It returned me to memoir rather than releasing me into fiction. So I allowed the story itself to suggest what was most central in what I was trying to achieve and found rooks rising to the surface of the historical narrative, reflections in the eye of a rook ultimately speaking to how they might be connected.

Now Eye of a Rook is in the world and my vulvodynia story is complete. My pain was not invited but it has brought me to this. How can I not be grateful?

Eye of a Rook by Josephine Taylor is available in all good bookstores and online.