Don’t give up your day job: why poetry has bad PR (and why you read more of it than you think)

When I signed my publishing contract with Fremantle Press last year, my partner immediately started joking about resigning from work – to wave celebratory pompoms at my book events and writers’ fests, soothe my perpetually poetically-furrowed brow, and make sure my favourite brand of poetry-inspiring beverage is always close to hand.

Show me the money satisfaction

But let’s not give up our day jobs. Studies show that Australian poets can expect to earn a ‘very modest’ income from our creative work (averaging $5,700 per year in 2020/21 – the lowest of all types of authors, though that’s not saying much).

Clearly, we don’t get into writing for the money. We do it because we have to, because we love it, because it’s how we think or communicate or make sense of the world. Sometimes, it can also help other dreams come true – like finding a tribe or an audience, sharing and developing our ideas, or seeing our words come to life on the page, stage or screen.

Excuses, excuses

I used to say my work as an arts manager was so creative and exhausting that I didn’t have the time or energy left to write. But after years of helping make other people’s dreams come true, I got sick of hearing my own excuses for why I wasn’t following my own.

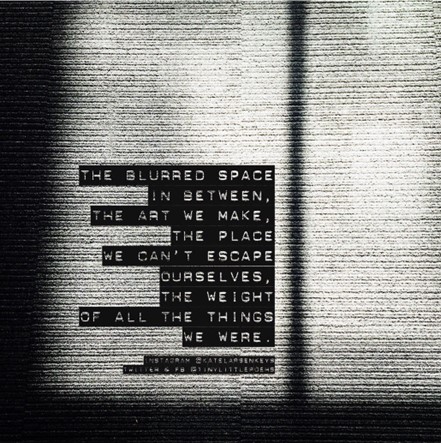

I set myself the deadline to write and tweet a #TinyLittlePoem a day – which turned into more than ten years of daily social media posts and a very large body of very small poems. It also exposed me to the extraordinary world of digital poetry, where innumerable global netizens – new and traditional poetry readers alike – opt into or accidentally consume poetry through their Instagram, TikTok or other social feeds.

This explodes poetry’s reputation as a niche or elitist art form, with the creation and consumption of digital poetry growing even further and faster since Covid-19, as more people turned to poetry to make sense of our ever-changing world.

For me, social media was the natural home for a decade of short, meme and video poems. Online, I not only found an unexpected audience, but a creative and supportive writing community, and a slew of surprising opportunities that included national and international poetry residencies and inclusion on an Oklahoman high school curriculum.

Our hybrid future

These days, we’re just as likely to find famous digital poets like Rupi Kaur, Lang Leav or Brian Bilston on the shelves of our local bookshops as much as we are online. But that progression isn’t linear. Digital poets aren’t sighing with relief at having ‘made it’ by finally seeing our words captured in print. With digital poems reaching hundreds of thousands of readers, the days of page-poetry being taken more seriously than poetry on the stage or screen are long gone.

Poetry is everywhere – in our TV ads and children’s books, music charts, birthday cards and social media feeds. Sharing digital poems in print is a celebration of hybridity and possibility, and an exciting cultural shift. Who knows how we’ll all be reading our poems by the end of the decade to come?