Author Michael Thomas shares how the silence of the past became The Map of William

The Map of William was the unintended outcome of a general curiosity about my own family history. As I became embroiled in the past lives of my forebears, my curiosity soon turned to something else. Not quite an obsession, but close. It became a search for details and evidence—the gathering of little snippets of information in order to find some truth amidst the rumours.

It began with Alexander Thomas, my great-great-grandfather. He was convicted of manslaughter on 28 February 1848 at the Swansea Assizes Court, and sentenced to fifteen years to be served at His Majesty’s pleasure in Western Australia. He arrived on 1 June 1850 on board the Scindian and on 29 May 1851 was granted a ticket of leave, allowing him to live his life in relative freedom. He married a fine woman, Louisa Caporn, fathered nine healthy children and was a skilled carpenter and shipwright. Alexander Thomas was many things, a murderer not the least of them, and a man fortunate to escape the hangman’s noose.

There were details to be found in documents and newspapers, prison records and court proceedings, obituaries and genealogies, biographies and letters—information tucked away in a thousand rabbit holes. Alexander was five feet and nine-and-a-half inches tall with light brown hair, hazel eyes, a tanned complexion and a middling, stout build. He was ‘adorned’ with tattoos— a woman with a rose in hand, an anchor on his right arm and two rings on his fingers, a cross and fish, an anchor and sun on the back of his left hand. There were small scars on the outer corner of both eyes.

As to the measure of the man, convict register details provide an insight. In reference to Alexander Thomas: ‘Of the few of whom I cannot speak with hope of an improved work and of general good conduct in future, is this man – he betrays much levity of both manner and language in subjects that should afford grave consideration, and affects much indifference about his future proceedings – however I hope he may amend in these respects …’

Alexander married Louisa Caporn, the daughter of Samuel Caporn who became a prominent man in the colony. The Caporn family arrived onboard the Simon Taylor on 20 August 1842. On the voyage to Western Australia, eighteen boys from Parkhurst Prison, aged thirteen to sixteen, were placed under the care of Samuel Caporn, my great-great-great-grandfather. The harrowing story of the boys from Parkhurst is worthy of its own anthology, but what of Samuel Caporn? He continued to invest in the lives of the young men in his care and his obituary in the Inquirer and Commercial News immortalises the quality of the man.

‘We notice with regret the death of Mr. Samuel Caporn, for many years past a resident at Fremantle, where, for nearly a quarter of a century he performed for us the office of agent for our journal at the Port. Mr Caporn died at his residence in Cliff Street on Saturday morning, at the good old age of seventy-four. He was buried in the Church of England Cemetery on Sunday afternoon, followed to the grave by one of the largest and most respectable assemblages of townspeople ever witnessed on a similar occasion in that town. Ever active and, above all, most scrupulously honest, Mr. Caporn continued to follow up the demands of the multifarious duties peculiar to his business to within a few days of his death, when exhaustion from diarrhoea overcame him, and he gradually sank, not without however, the most sincere and heartfelt sorrow not only of his fellow-townsfolk, but of the community generally, as an honest, upright, and most worthy colonist.’

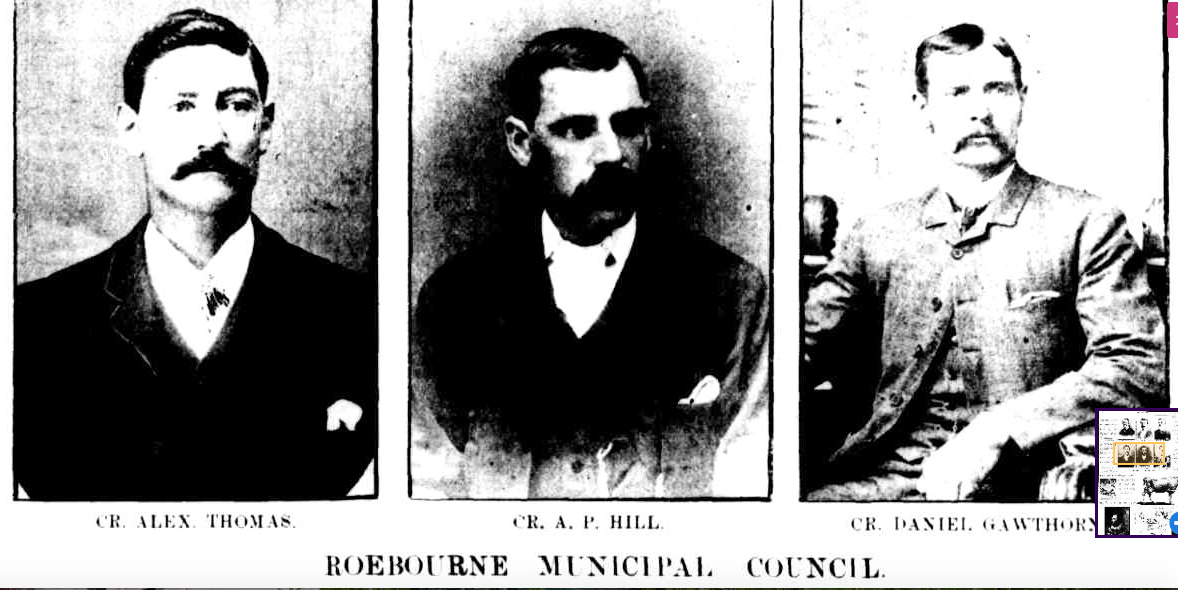

In 1905, my great–grandfather, Alex Thomas fell from his horse on the road to Cossack and died a short time later. According to the anecdotal history of the Thomas family, Alex was a handsome man, a fine husband and father and a savvy businessman with a sharp mind and an even sharper sense of humour. He was husband to Martha Hayden, my great-grandmother who was a force of nature according to the family rumour mill. They married in Roebourne in 1887 and together produced eleven children. Three died in infancy and a son, Sydney, died in 1898, aged six. Alex and Martha Thomas endured tragedy and tribulation and for my great-grandmother that tragedy was compounded by the death of her much-loved husband at the age of thirty-seven. Their lives are acknowledged and celebrated in The Map of William, and part the inspiration for the characters of Hywel and Louisa Watson.

Alex rose to prominence and was elected to the Roebourne Municipal Council where he served with distinction. At the time, Roebourne was the pre-eminent town in the northwest of the state, serving a thriving mining and pastoral industry. Alex had several business interests and the local butcher shop was one of them. There is a moment in novel where William writes, ‘The butcher shop had its share of trade and I winced at the smell of offal as we passed by. Mother had become adept at making sausage from the foul-smelling entrails, which she declared was a Welsh version of black pudding. Smell and memory had combined once more and for a fleeting moment, I thought of home.’

The Map of William is full of nods to Thomas men and women, past and present. At one point in the novel, William makes an observation in reference to his first impressions of the town of Nullagine. ‘I could not help but wonder why men would leave hearth and home for a place such as this. To come from green fields far away with no sure promise of reward, toiling from sunrise to day’s end, with lungs assaulted by swirling dust and minds numbed by the monotony of it all.’

My great-great grandfather Alexander is buried in the Nullagine cemetery. He died at the age of sixty-six from the effects of sunstroke and was laid to rest by friends and strangers. Far from home and in such an isolated place, no one from his family attended the funeral. Hywel Watson tells his son, ‘No life should pass unacknowledged, William. Not a stranger or a friend. No grave should remain unmarked and untended.’

At the time of her death in 1910, my great-great grandmother Louisa Thomas was also immortalised in an obituary in the Western Mail on Saturday, 2 April 1910.

‘Another old colonist has passed away in the person of Mrs Louisa Thomas, at the age of seventy-three years. The deceased lady arrived in Western Australia with her parents, when five years of age, in the ship Simon Taylor in 1842, having resided in this State for sixty-eight years.

She was a granddaughter of the Reverend Joshua Caporn, niece of the Reverend James Caporn, cousin of the Reverend C Goode. She had nine children, sixty-five grandchildren, and thirty-two great-grandchildren. In all, one hundred and six direct descendants.’

My grandfather, Raymond Thomas, was one of those descendants. He stayed on in Roebourne where he married Ethel Kain and worked hard to support his growing family. My grandparents lived their lives and battled through the Great Depression, suffering enormous hardship and loss, like so many others. My father Roy was born in 1918, went to war in 1939 and settled in Carnarvon to raise his own family—the circle of life. Roy became a shearer and I spent my formative years bouncing around the Gascoyne, Pilbara and Murchison regions of Western Australia working as a roustabout and sometime drover. It would be fair to say that the land where William walked is in my blood.

I had thought to write a selection of short stories, the best and worst of us—the murderers and the highwaymen, the butchers and the soldiers, the mothers and the daughters and those who died before their time. In the end, I settled for one—The Map of William. I took William’s name from the youngest of Alexander and Louisa’s children and bequeathed it to William Watson, the hero of my story. It became a deeply personal reimagining of many Thomas lives, and William’s expedition north is a mirror to my own journey of discovery.

There is treasure to be found in our own backyard—stories worth telling, and they are ours to tell. I thought that I might take William Watson to war in the next part of our journey together, to acknowledge and remember my forebears who are buried far from home.

References

Australian Joint Copying Project. Microfilm Roll 92, Class and Piece Number HO11/16, Page Number 176 The Perth Gazette and Independent Journal of Politics and News 1850 Jul 26 p/4: (Convict Records 779-783. Alexander was convict 61: R 21A/ 1156 State Records Office Microfilm)

Cardiff & Merthyr Guardian, ‘The Murder in Whitmore Lane’, 1848

Inquirer and Commercial News (Perth, WA: 1855–1901) Wed 26 Feb, 1868– Page 2: http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/69386607

Midwest of Western Australia Heritage: https://midwestwaheritage.com/resultmcr/?id=2092

Newspapers and Gazettes, Western Mail: Friday 27 May, 1898, Page 33, Roebourne Municipal Council https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/33152564

Western Mail, Saturday 2 April, 1910. Obituary, Mrs Louisa Thomas