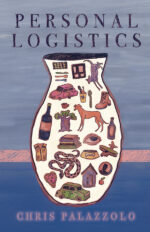

New collection opens a window onto the impact that human beings have on the natural world, and the uncompromising power the natural world can assert over human endeavour

Personal Logistics details the poet’s experiences and observations of life in Kununurra and the East Kimberley, as someone who has worked as a farmhand and as a stay-at-home dad. Coursing through the collection, in both the wet season and the dry, are the dual themes of naturally flowing water and hydroelectricity, without which Kununurra would be considerably less hospitable. Publisher Georgia Richter asked Chris Palazzolo to tell us more about the book and the inspiration behind it.

Is it your experience that you need to write poetry in order to understand your relationship to place?

All of my writing, not just poetry, is to some degree chasing down a sensation of place. The writer’s privilege is that any place becomes meaningful because the writer inhabits it, writes about it, inflects their descriptions of its features through the prism of their (or their character’s) interior states. My conception of ‘place’ is a kind of civic consciousness. I have always considered myself a Perth writer and felt my responsibility to the city is to use the features that attract me – its street corners, footpaths, freeways – as elements of an intellectual landscape. This is not as obvious as if first sounds; Perth is rarely thought or spoken about intellectually (contrast this experience to that of a Melbourne writer, who would take for granted their city as an intellectual landscape). Now that I live in Kununurra, I observe the town’s forms with the same ‘eye’ – which means I feel a certain detachment from it. I am always conscious of my home city 3300 kilometres away. ‘Place’ now means exile.

At what point did you begin to think of individual poems as ‘a collection’? Did this affect what you wrote next?

Moving to Kununurra has been creatively successful for me. My last few years in Perth were somewhat barren; apart from diaries, I wrote very little. I don’t know why this was, but I was in a deep rut. As soon as we settled here, I began writing again, at first continuing the diaries, then letters and essays, and then poems, which came thick and fast (by my productivity standards anyway). For this reason, I was conscious very early on that I was building up a distinct body of northern Australian verse. Over the following years, the collection silted up; I would fill a notebook with drafts, work on them for a couple of months, stop and attend to other things like work and kids and travel, and then I’d take up my pen and fill up another notebook, and so on. The novelty of what I was experiencing largely determined what I wrote – seeing Wyndham and the Cambridge Gulf for the first time, or holidaying in Katherine and Darwin. Only when Fremantle Press took an interest in the poems did I begin to think of an arrangement.

What is a poem that you have ‘stitched and unstitched’ multiple times? Where did it begin, and where did it end?

The most troublesome poems in the current collection were the two ‘Tribute’ poems and ‘The Last Streetlight and the Inexpressible’. All three sprung from a single draft in one of my 2020 notebooks. The original draft was a kind of cursory sketch musing on the streetlight at the end on my driveway and the source of its power – the Ord River hydroelectric plant seventy kilometres away. I have always been intrigued by the poetic possibilities of streetlights, their ‘exteriority’, and a kind of socialistic collectivity of electrons and photons extracted from a lump of coal (a primeval tree) or a mass of water, that results in illumination which sculpts visible forms in the night. But the sketches were too abstract, too thin and obscure; I just couldn’t make them work. It wasn’t until 2023, when I started thinking of an arrangement and a kind of unifying motif for the collection that all three took their present forms. They now serve as a thematic continuity between this collection and my first volume of poetry, Unhoused (Regime Books, 2013), which used a recurring motif of a piece of coal burning in a chamber as a unifying principle.

Do you have a favourite poem in this collection?

In his Annals of Imperial Rome, Tacitus said of Emperor Claudius: ‘Claudius continued to make decisions based on advice he received last.’ When it comes to my poetry, I’m like Claudius; my favourite poem is always my last one. I’m particularly pleased with ‘Songlines and Sandy Floors’, because I knocked it off in a couple of sittings, out of a very unpromising sketch, just a day or two before the manuscript went to print. I know it’s not the best poem in the collection, but I’m still getting a buzz from looking at it.

Who are the poets you read, and why?

The only poet I examined in depth (that is to say, their body of work and a biography) was the Italian medieval humanist Petrarch. My honours thesis was an analysis of his collection of Italian verse (most of his writing was in Latin) known as Rime Sparse, or Canzoniere, which largely, though not exclusively, dealt with his unrequited love for a married woman. All of the examples I analysed I translated myself (with the help of Professor John Scott at UWA) from Petrarch’s very colloquial fourteenth-century Italian into modern English. Translating these sonnets, odes and sestinas was like opening up jars of preserves that have sat on dusty shelves for seven hundred years; the smells that came out of them were quite heady – the lustful stink of a cloistered scholar.

Individual poems rather than poets as such have influenced me more. Just a few I’ll mention briefly (there are links or copies below). They include the Irish poem, ‘Landscape with Figures’, by Frank Ormsby and ‘The Man Who Read Skies’ by Mardi May. Others are ‘The Idea of Order at Key West’ by Wallace Stevens. I love the music of Stevens’ language, the way it rolls with the sea and ‘Parnell’s Funeral’ by W. B. Yeats – a jeremiad against the demagoguery of Irish nationalist politicians, as relevant today as it was back in 1922.

Personal Logistics is available in all good bookstores and online.