Translating Salt River Road by Molly Schmidt: from Australia to Italy and return

by Alessia Carbonaro

As clichéd as it may sound, I believe that some stories find their way to us at exactly the right moment. For me, Salt River Road was one of those stories. Drawn by its cover and title, I first picked it up from the New Releases shelf of my local library in Melbourne, where I was doing my study year abroad in 2023. What began as a casual read soon became something much more—a story of loss, healing and reconciliation that stayed with me long after I turned its final page. When it came time to choose a work to translate for my master’s dissertation, I found myself revisiting this novel through a translator’s lens, inspired by the unique translation challenges it posed.

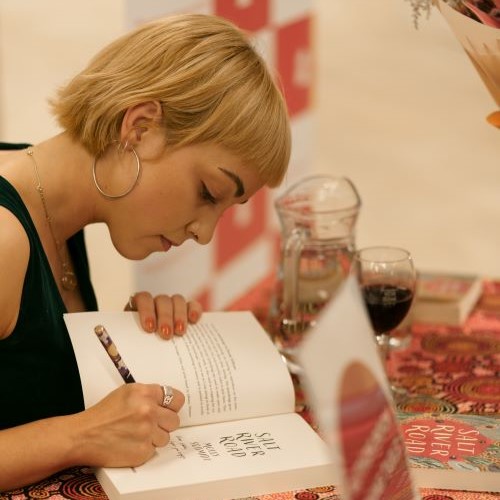

Translating Salt River Road may have started as an academic exercise, but it soon turned into an incredible personal journey. I was able to travel to Western Australia between September and October 2024 to meet and work with its author, Molly Schmidt, as well as visit with her the places where the novel is set and learning more about the Traditional Custodians of south-west Western Australia – the Noongar people, and their culture. This experience helped me view the book from new perspectives and enabled me to better navigate its many translation challenges.

One of the most rewarding parts of the process was translating Australian slang. Dialogues and descriptions in Salt River Road brim with references to Australian realia and colloquial expressions, some of them popular in the 1970s, when the novel is set. These include ‘ute’, ‘Hills hoist’, ‘pink-and-greys’, and at a more local level, ‘doing a yorkie’. All of these elements came especially alive for me when Molly showed me around Albany and Mount Barker, the place on which the novel’s town is based. Not only was it a challenge to maintain the colloquial tone of these words, but in many cases, no equivalents existed in Italian. To ensure understanding while still preserving the authenticity of the setting, I often resorted to short descriptions: for example, a ‘Hills hoist’ became ‘stendino rotante’, a rotating clothing line.

Perhaps the most delicate challenge lay in the novel’s references to Aboriginal Australian history and Noongar language and culture. Many Italian readers may lack familiarity with this context, so I sought ways to convey these elements clearly and respectfully, for example by keeping the Noongar word ‘boodjar’, which Western Australians translate as ‘country’, and then adding its Italian translation, ‘territorio’. Similarly, I kept the names of Australian native plants in Noongar language and Latin, and only translated the English name into Italian where an equivalent word was available.

Another challenge was the novel’s alternation between prose and poetry, each form serving a distinct purpose within the narrative. Translating poetry requires a different approach to prose, as meaning is also derived from the emphasis on form and deliberate ambiguity caused by line breaks or multiple associations. In my first draft, I prioritized the meaning and then revisited my translation to ensure the rhythm and emotional impact of the source text were maintained.

Translating Salt River Road was a challenging and rewarding journey, made even more enriching by the opportunity to visit WA and work closely with Molly. This was an exceptional privilege, as not every translator is fortunate enough to immerse themselves in a novel’s world or engage directly with the author. Incorporating this direct experience into my translation gave me a richer, more intimate connection to the text and helped me ensure that an Italian target audience could connect with the story as powerfully as I had, without losing the essence of what made it distinctly Australian.