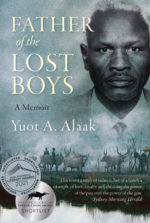

Yuot Alaak – City of Fremantle T.A.G. Hungerford Award Shortlist

Read an interview with City of Fremantle T.A.G. Hungerford Award shortlisted writer Yuot Alaak and read an extract from his book Father of the Lost Boys.

Describe your manuscript in your own words.

Father of the Lost Boys tells the story of my family and especially my dad, Mecak Ajang Alaak, who led almost 20,000 unaccompanied minors out of danger during Africa’s longest civil war. It is an eyewitness account by me, who trained as a child soldier and walked by my father’s side, clutching an AK-47 as I slept next to him.

Before taking on his central role with the now-famous Lost Boys of Sudan, Dad was a prominent educator imprisoned by a government which served its own propaganda interests by announcing his death over the radio. We conducted his funeral, only to discover he was still alive. Dad returned to a hero’s welcome and to one of the most challenging tasks imaginable.

The story follows the Lost Boys as they journey through rainforests, savannah and desert to escape war and devastation. I saw my father at times of immense stress, but also witnessed his determination to guide the Lost Boys towards a brighter future. Although many succumbed to starvation and thirst, drowned in treacherous rivers, or died as the result of aerial bombardments, landmine explosions, gunshot wounds and wild animal attacks, the majority of the Lost Boys survived. Their story is of global significance and has featured on the BBC, CNN and the Oprah Winfrey Show. But Dad’s remarkable story as leader, teacher and father of the Lost Boys has never previously been told, until now.

What inspired you to write it?

Maya Angelou! Her words, ‘There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside you’ rang true to me. I wrote this story to free myself of that agony. I’ve refused to let my past define my future but I think this is an important story and I believe it will resonate with many of my fellow Aussies – most of whom have their own migrant stories, dating as far back as 1788 or as early as yesterday.

How long have you been working on it?

I’ve been wanting to write this story for what seems like an eternity but I only started to get serious in the last twelve to eighteen months. My romantic fantasies about the writing process have since been thrown out the door. Writing is quite a slog but the joy of seeing a story come to life far outweighs any pain, which for me was quite emotionally draining at times.

What does it mean to you to make the shortlist of the 2018 City of Fremantle T.A.G. Hungerford Awards?

It means a great deal and is beyond my wildest dreams! I sent in my manuscript knowing the chances of making the shortlist were pretty much non-existent, but I used the submission deadline as motivation to keep writing. I’ve grown up hearing, ‘Maaate! You’ve got to be in it to win it’, so I submitted and I am super stoked at making the shortlist.

From Father of the Lost Boys by Yuot A. Alaak

Madiba marries Mary with whom he has two children – the youngest daughter, Atong, and me, Ode, her first-born son. I am named after my great-grandfather. I become aware of my father’s stature in the community from an early age, and can see the reasons for it. He is tall, dark and handsome with a strikingly athletic build. His smile is white, wide and glorious. He is calm and collected, and has a powerfully visionary character. He is convinced that nothing can stop the people of South Sudan from realising their dreams. South Sudanese people come from numerous tribes, but are a strong-willed and united people.

Dad’s dreams are shattered while he is in the capital, Khartoum, organising supplies for southern schools. It is May 1983. The President of Sudan goes on national radio and, to Dad’s dismay, announces that he has torn up the peace agreement that has given the south of the country autonomy, recognising her black African ethnic composition and religious diversity. The president’s voice streams across southern airwaves: Sudan is one country. From today, all must speak Arabic and adhere to Islamic Sharia law.

Southerners are poised to be ruled by a religion they know nothing about. They are to speak a language foreign to their lands. It is something they have rejected in the past, and they are ready to reject it again. They will not abandon centuries-old cultures, their languages and beliefs for a religion they know nothing about, and a language they do not understand.

There is a mutiny in Bor Town, pitting southern soldiers against troops from the north, sent to enforce the orders of the president. The fighting kills scores of people. Bor Town is abandoned as thousands flee. My family escapes into the bushes,too, but Dad is still in Khartoum, thousands of kilometres away. At five years old, I have been separated from my father. We walk for days, finally arriving in our home village of Majak in Twic East County, some one hundred and thirty kilometres north of Bor Town. We make it to Majak because relatives take turns carrying me. Mum carries Atong on her back, our food basket on her head.

Majak is beautiful. The landscape is covered by acacia trees. Often, we watch cattle graze languidly on the lush green pastures that extend as far as the eye can see. The sun rises and sets over the horizon at the same time each day. It is a tranquil paradise, far separated from the war that rages around. I meet many of my relatives for the first time – grandparents, uncles, aunties, and seemingly a million cousins. They’re all immediately fond of me, fighting for my limited attention.

I soon learn that I am not a natural at village life. I am afraid of goats and chickens. I struggle to adjust, but eventually adapt and begin to thrive. I start to look after our goats. I begin wrestling with other boys. I become close to my grandparents, spending countless hours with them.

Despite the veneer of normality in Majak, I have grave fears for my father. He has not been able to return since we fled Bor Town, his desperate attempts to sneak out of the north unsuccessful. Occasionally, we hear some rumour that he is safe, or that he has been spotted in this town or that town. But I miss him and my fears are unrelieved.

After about three years, we get a letter stating that he has been smuggled out from the North. We’re told he’s hiding in a safe location but that the security forces are looking for him. Because of the war, thousands are trapped in different locations across the country. No one can travel from one part of the country to another without putting their lives in grave danger. Dad’s return is impossible under these circumstances. He is working underground in the state of Upper Nile for the South Sudanese resistance against oppression from the North. He is wanted by the Islamic government in the North for his refusal to teach Arabic and for teaching English instead. Malek, his school, has been taken over by soldiers. Schools are now used as military barracks across the south. Many of his students have taken up arms to fight for the South. I cannot begin to imagine how it must pain him that the pen is being replaced by the bullet.