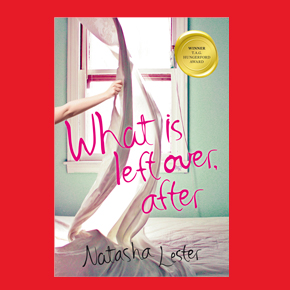

Read this and be smarter: an extract from the Hungerford Award winning book that kickstarted the career of New York Times bestselling author Natasha Lester

What is Left Over, After was Natasha Lester’s Hungerford Award winning debut novel back in 2008. These days she’s topping the bestseller list of the New York Times, as well as offering advice to new and emerging authors.

You can catch Natasha at the Business of Being a Writer event at Perth Festival Literature and Ideas Weekend to hear her thoughts on why every writer should enter the Hungerford Award. But for now, check out the extract below to find out why her first novel is worth getting your hands on.

……..

I was six years old when my mother came to collect me from my grandparents’ farm in France as if I were simply a piece of luggage that had been misdirected. I had never expected to be granted a mother-creature and only knew of their existence because the children on the neighbouring farms all had one and because I had heard about them in fairytales: mothers died tragic deaths so their children could be persecuted by evil stepmothers, or they made promises to give their children away in return for magic powers. Knowing this should have made me more careful.

On the morning my mother was to arrive I woke early and went downstairs to the kitchen where Pépé was sitting at the table with a bowl of café and a hunk of bread and pâté.

Mémé smiled at me as I walked into the kitchen, her face rippling with lines like a puddle. ‘Why are you up so early, chérie?’

‘Because Maman is coming today.’

Pépé gulped the rest of his café, stood and left the room, leaving behind a trail of breadcrumbs. I moved to follow him, to demand my morning kiss, but Mémé propelled me into a chair.

‘Pépé is busy today. Have your breakfast.’

That accomplished, I set off along the track cut through the long grass by Pépé’s van to wait at the gate for the arrival. I watched, for what I thought was a long time, the dirt road that linked our farm to civilisation but the dust remained still, unstirred by car tyres. I closed my eyes and listened for unfamiliar sounds amidst the goats’ bleating. Nothing.

As the sun rose, my legs began to tire and my skin to sweat. Dust stuck to my face. I itched. I was sure it was lunchtime but I knew that if I turned away, then she would arrive and I would miss the spectacle.

‘Gaelle!’ Mémé was approaching. ‘Time for your nap.’

I shook my head and clung to the gate. But Mémé’s arms, made strong by years of herding goats, prised my fingers away, lifted me up and took me home to bed.

I woke to an unfamiliar sound, like pebbles shifting on a shore. I listened for a minute, realised the sound was laughter and followed it out to the kitchen.

A crowd of aunts, cousins and uncles from the neighbouring farms was gathered around the long oak table. Rows of copper pots flashed into the room like miniature suns and my nostrils filled with the fresh, charred scent of Pépé’s goats cheese. A stranger was seated at the head of the table and I watched her as she spoke.

‘I wore false eyelashes, and ostrich feathers in my hair, and every night I danced the cancan in the biggest casino of all where the hotel rooms had round beds raised on plinths, satin sheets and mirrored ceilings. Vegas is like Paris surrounded by desert. Full of light.’

When I was six, I had never heard anyone talk like my mother. I remember turning my attention to my aunts and uncles, expecting a boisterous outburst of mockery. But there was only the bubbling sound of expectation. They were spellbound. Was it because of the tale she was telling or the way she looked? Both were equally unexpected. Feathers and false eyelashes were as common in our village as the blue satin shorts, brief as underpants, which this woman wore.

Now, looking back, I wonder if my relatives were not actually captivated. Perhaps they were simply afraid to interact with someone who’d become known as the black sheep, scared that her blackness would contaminate them with its exuberance, its absence of limitation. Or they could have been suppressing floods of scorn at her inappropriateness; what use, after all, are oriental embroidered clogs when one has to traipse all day through dust and caca.

I must have made a sound and betrayed my spying because Mémé held out her hand to me. ‘Gaelle! You’re awake. Here’s the person you’ve been waiting all day to see.’

She patted me in the direction of the barely dressed sorceress, who opened her arms. I was transfixed by her fingernails, which were long and gold and therefore made for casting spells. I stood back and waited, assessed. Perhaps that was my mistake. If I’d run straight into her arms like a good daughter should, then everything would have been all right. The mother–daughter bond would have conquered all.

Before I had decided what to do, Pépé stood and said, ‘Gaelle needs to come with me. Check the goats. There might be a storm.’

He picked me up before my mother could reply and carried me out to the hall. He stopped only to get our boots and to put me down and then he began to march away, towards the forest, so fast that I had to run like the dogs at his heels to keep up. Pépé slowed to lift me over the wire fence and only began to walk at my pace once we were tucked away into the trees.

The forest was bedded down, ready for slumber. The silence hurt my ears after the fullness of sound in the room we had just left so I said to Pépé, ‘Why is Maman here?’

He bent down, picked up a rock and passed it to me. ‘Gaelle, what colour is this rock?’

‘Grey. But why …’

‘Or is it blue?’

I laughed and was about to say no, but I stopped. The top side of the rock, coloured by light tipping through leaves, did have a bluish hue.

‘What colour do you think the rock will be if we come to find it tomorrow morning?’ Pépé continued.

I thought for a moment. Mornings were usually muddy, the colour of truffles. Perhaps the rock would be too. I was about to say so but he did not wait for my answer. ‘Things always change, Gaelle. Even here. Some changes suit us, some don’t.’ He dropped the rock and then said something I’d heard him say so many times before, usually after too many bottles of vouvray. ‘I’m an accidental farmer, Gaelle. I was going to catch the train to Calais and then a ship to New York. See the Empire State Building. But responsibility caught me first.’

I used to wonder what this responsibility was, what it meant. Now I know. A farming legacy left by his parents. A dead older brother. Also me. And Maman.

My six year old self dreamt that night about being locked in a land inhabited only by my mother. The land shifted and moved and nothing there was familiar except the repetitive sound of an unknown voice, like a nursery rhyme.

I woke up with the shifting feeling inside my stomach; it made me catalogue my room as if it too would soon shift away.

There was the torn but still beautiful silk-covered dressing screen that Mémé said had protected the modesty of young women for hundreds of years. Mémé also said it was the one remaining treasure of our house’s former glory. The screen was embroidered with castles and peacocks and tournesols — sunflowers — with their heads lifted up to the sky. And the walls of my room were heavy, pungent with bouquets of peeling wallpaper.

As I remember this, I want to laugh because now, of course, such things are fashionable and dozens of shops in Woollahra sell imitations of the furniture and accoutrements of my childhood. Back then, our version of French shabby chic was merely shabby and not at all chic. How artificial the items in those shops now seem, the artifice intensified by the rooms in Sydney to which they are transferred — there is too much openness. The genuine articles are meant for rooms caught and bound and walled; the space of an open plan has a temporary feel at odds with timelessness.

Then I began to hear real voices, loud voices, voices caught and bound in the rooms downstairs, so I slid down the stairs and sat on the floor behind the closed kitchen door.

‘I have a wonderful new job without so much night work. And good money. I can look after Gaelle.’ It was my mother’s voice.

‘What is this wonderful new job, Lili?’ It took me a moment to work out that this was Pépé’s voice. There was a tone to it that I had never heard before.

‘I don’t have to explain everything to you. My word should be enough.’

‘Your word! The word of a mother who abandons her child is worth nothing.’

‘I want to get to know my daughter.’

‘If you take her now, she’s yours. We don’t want you back.’

My mother’s voice snapped like broken bone. ‘I won’t ever be back.’

She marched out so quickly that I didn’t have time to slip back to my room. She saw me there, laughed and squatted down to tuck a piece of hair behind my ear. ‘Gaelle, we are the same, you and me.’

At the time, I did not understand it was a wish rather than a prophecy.

What is Left Over, After by Natasha Lester is available as an ebook from the Fremantle Press website

The Business of Being a Writer

Saturday 22 February 2020

9.30 am – 2 pm

Winthrop Hall Undercroft, University of Western Australia, 35 Stirling Hwy, Crawley, WA

$29.99 + booking fees

Bookings via Perth Festival website