Is writing good sex hard work? An editor’s thoughts on love (Part 1)

When the curtains don’t match the carpet

‘It glinted like the Star of Bethlehem as the throbbing incandescent light strips of the office hit his winkle with a twinkle. Belinda dove into his pubes, running the ringlets through her fingers like grated carrots.’

– Rocky Flintstone, Belinda Blinked, 2021 Christmas Special, Part 1.

What is the difference between the genres of porn and romance? In a word, the answer might be ‘love’ – though, in more words, the answer might be ‘frequent gratification’ versus ‘gratification delayed’.

There was a time when my friend Fran and I – aged fourteen – thought we’d write a Mills & Boon novel. Having grown weary of pamphlet delivering, we got into the romance writing game for the Big Bucks. We did not stop to wonder how two girls in ski pants, winklepickers and paisley ties, who had not yet kissed anyone, would have the writing chops for the job.

It’s not that we weren’t at home with metaphors or even plot ideas – we spent hours on holiday driving Fran’s parents up the wall with frivolous fancies – but we had no idea until we tried how hard it was to write about how hard it was.

Not only did we not have the lived experience to create pulsating sexual tension, we also found ourselves unable to check our irony at the door. One had to be sincere in the endeavour, we realised as we floundered, and we were there for all the wrong reasons.

Over the last few years, I have been paying gleeful attention to bad sex scenes while listening to the Belinda Blinked series in the long-running podcast My Dad Wrote a Porno. As any Belinker knows, this is where the genre of satirical porn (or is it?) with a business-advice twist has been polished to an incandescent sheen.

When it comes to writing sex scenes, Belinda Blumenthal’s creator, Rocky Flintstone, uses whatever metaphors he damn well pleases, but he does it most sincerely and with faultless enthusiasm. The boulevard down which he wantonly scampers might be signposted So Bad It’s Good.

My own desire to write anything with sex scenes has fizzled, but I remain fascinated by a writing skill in which performance counts, and faking it is not an option.

As an editor, I have some experience helping authors rectify ill-executed sex scenes. Often in language (as in life) it comes down to a matter of self-control. I wish I could share some of the dreadful scenes I have encountered in the slush pile, but I won’t (what happens in the Slush Pile, etc.) Suffice to say, sex scenes are bad often because a writer feels uncomfortable, and overcompensates. They overreach, or deploy a metaphor that makes their characters look foolish. Some sex scenes are lascivious sheep clad in wolf’s scanties. A few writers, like Rocky, eschew editors, but have somehow managed to make bad sex-scene writing into an artform.

In Belinda Blinked, Belinda has egalitarian, unflappable, transactional sex, and she has it often. Even so – and even though Rocky is frank about the shortcomings of penises, and he embraces embraces of other kinds – it remains that Belinda is written by a white cisgender male. Rocky’s style of porn feels like his fantasy, and the phallus dominates his oeuvre.

Rocky lays down sexual metaphors with a stunning biological ignorance (genuine?) that startles the listener into appalled laughter. Famous among them are nipples like rivets on the Titanic, and female genitalia flying open like ‘lids’. In Rocky’s most recent Christmas special, we are told that ‘the curtains don’t match the carpet’. Which is to say, Paddy O’Hamlin’s red hair upstairs reveals itself to be rust-coloured down below, where the ‘carpet’ has been laid in thick ringlets that themselves are like ‘grated carrots’.

Rocky’s metaphors remind me of a teapot I once knew that was in the shape of a handbag, which was in the shape of a crocodile.

A rose by any other name

One of my favourite pastimes is sitting down the back of the Salvos store on a vinyl couch perusing Mills & Boon / Harlequin titles like these:

- The Flaw in His Marriage Plan

- Tempted by the Brooding Vet

- Unwrapping the Neurosurgeon’s Heart

- Pregnant Midwife on his Doorstep

- Risking it All for the Children’s Doc

- A Forbidden Night with the Housekeeper

Why do I love these titles so much? Precisely because they are so prosaic, and because they go against everything I, as a publisher, strive for. In my world, I look for titles with layers of meaning, and energy that resonates. But with romance titles, you get what it says on the label. Maybe that’s the point: they are designed to be consumed in bulk and the only way the consumer can tell them apart is if the synopsis is the title.

Looking at these titles makes me curious about what’s hot and what’s not. Right now (in the op shop world) there are an awful lot of Mediterranean tycoons / widowed doctors with babes in arms, who with one hand are trying to operate on people’s hearts / run a furniture import business while feeding a newborn baby with the other. Why does the guy have to be filthy rich, and left with a motherless child? Austen knows, the pay-off is much greater when the (apparently) unlikeable hero is filthy rich but Mr Darcy never showed up on his stallion at Longbourn wearing an infant strapped into a BabyBjörn. Clearly something has happened to romance since 1813.

Speaking of Pride and Prejudice, it’s clear the titles weren’t always so workmanlike. I recently read Serenade for Doctor Bray by Juliet Shore, published by M&B in 1964. What differences does one find in an M&B that is over half a century old?

Without doubt, Ms Shore has superior writing skills to Mr Flintstone, and she executes a plot that does a couple of unexpected pivots. Unlike Rocky, Serenade demonstrates a chaste approach to sex that is full of tension but never makes it past the kissing.

A dominant-male / submissive-female theme shines through. Our heroine Frankie finds it ‘wonderful to be overruled by somebody as masterful and kind as Doctor Bray’ (whose first name is Dickon, and who owns a dog called Girlie). Frankie’s sister Rosalind exhibits some classic ‘feminine’ wiles: ‘a cooing siren one moment and a hissing serpent the next’. Ros turns out to be a bitch in serpent’s clothing, who only pretends she wants to marry Dr Bray in order to thwart her sister Frankie.

A disturbing note (for a Mills & Boon) is struck by the author early:

‘It wasn’t that [Frankie] didn’t love Ros, and she would really miss her if they were separated, but there would be compensations, as a young tree in a wood is compensated by the kiss of the sun when an overshadowing neighbour is summarily removed by the feller’s axe.’

In this metaphor, Frankie is the young tree – and the kissing sun, I suppose, is Dr Bray. One can surmise that Ros is heading for calamitous trouble. Indeed, the authorial axe of Shore takes to the tree of Ros in the form of a car crash on the edge of a cliff. (Disappointingly, Ros survives, so they can all live happily ever after.)

What’s love got to do with it?

Having spent some of the festive season watching my daughters watch Twilight, it seems to me that ‘love’ is the word that people use in romances when sexual gratification must (for whatever reason) be delayed. ‘Love’ helps to explain the feeling one has when one can’t have sex. It’s also the word for the feeling that a vampire has when he is trying to stop himself from eating his girlfriend.

The closest I have come to this feeling IRL was the night of my first COVID vaccination when (at the conclusion of a horrible aching fever) I developed an insatiable desire for roast chicken. The difference between Edward Cullen and I is that if Jeeves hove into view at 4 am bearing a chicken and some piping hot roast potatoes, I would have tucked in. But Edward must resist Bella because it would be fatal to have her. He loves her because it is the only thing he can do while gratification is delayed.

Of course, I understand that delayed gratification = obstacles = plot, but the word ‘love’ sometimes seems like a convenient shorthand for the promise of ‘you will get to have great sex at some stage if you just stick around’.

Reading M&B, I find myself with lots of questions about the genre. Is writing good sex hard work? Is it possible to write a romance in a feminist way? Most of all, I would like to ask an M&B author about the question of love. What are we to make of a book about ‘love’ if that ‘love’ feels like delayed sexual gratification and an escapist fantasy?

At the end of Serenade, the happy union comes not only for Frankie and Dickon, but for Rosalind too, who, while in a post-cliff coma, has attracted a chap called Connaught. He is described by Dickon as ‘no fool’. Moreover, says Dickon ‘he’ll lick her into shape when she needs it.’

The book draws to a close with the masterful men ready to control (or lick) their women when they ‘need’ it – and by the penultimate paragraph, we have reached the cusp of the happily ever after:

‘Tomorrow was the time for making plans, for forgiving Ros all the ill she had caused and seeking her out and wishing the newly-weds all happiness: tonight was for kissing and dreaming and living in the eternity of the wonderful present.’

But isn’t all the carry-on about true love just because the couple is still waiting to have a good bonk? If I learnt anything from Twilight, it’s that shit only gets real when the woman gets pregnant and the baby tries to destroy her from the inside out and the bad vampires return to town.

Let me count the ways …

Don’t get me wrong: I have been fortunate enough to fall in love – I have been in the state of can’t-eat, can’t-sleep; choosing somebody and feeling chosen in return; waiting for the anticipated union so the rest of my life can begin. It’s hardly surprising that this state of being-in-love – so exquisite, and so outside the realm of how we ordinarily function like regular, sensible human beings – is the subject of a long-running, mass-marketing enterprise. M&B know their onions. If readers are not in that state of being-in-love right now, why not read about it in somebody else’s life?

But what will happen to ‘true love’ when Dr Bray starts wearing cardigans and begins to snore, and Frankie slips over and breaks a knee on the wet porch while wearing her Crocs? Not to mention the fact that there are enough red flags in the ‘masterful man’ department to make me worried about what kind of unions Ros’s and Frankie’s will be.

The love I am accustomed to working with in the novels of my authors is a more diurnal kind. It’s the sort based on the cardigan and broken-knee phase of life. In the books I edit, authors often grapple with the love that exists when hearts are broken, and when characters lose, have to give up, turn away.

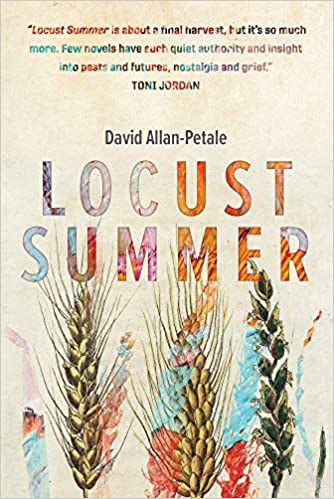

There’s a scene in the middle of David Allan-Petale’s Locust Summer, where Rowan finds his dying, dementing dad atop a big rock in the middle of their farm after his father has gone wandering:

‘There he was as if in a painting. Man on the rock, distinct to the dark as the headlights washed over his arms and legs and face and hands, yellow pyjamas, black leather slippers and white skin. He was sitting in the pose of a thinker, looking out over paddocks lit by the moon and the Milky Way. I killed the engine and the lights and climbed up there after him, finding the way by easy instinct. Up on top, I sat beside him and said nothing. There are only a handful of moments I can truly say that the whole of my attention was focused, where no stray ounce of feeling was on autopilot, rendered of any distraction.’

Rowan’s father talks and Rowan (for once in his life) properly listens. Then at the end, his dad says, looking over the farm he has worked all his life:

‘ “If I had my way, I’d let it all go fallow. Let the bush reclaim it. We have no business being here.” He looked down at me. “You got a cigarette, mate?” I did, and lit two. We smoked in silence, sharing the view, and I kept a hand on the boulder to steady my balance as the world spun faster and faster, louder and louder, till I felt like a rock tumbling through the air.’

Sometimes this kind of love looks like the thing you feel when you don’t want to feel it at all. This is the love that takes place in the difficult off-road terrain that lies beyond the golden path of happily ever after.

In Part 2: Georgia talks to Mills & Boon author Michelle Douglas