David Whish-Wilson says writing fiction means living with ghosts of his own making

The Sawdust House is my third historical novel, following on from The Coves in 2018. I’m normally a crime fiction novelist, but my crime novels have an historical element too, with most of them set in 1970s and 1980s Perth and Fremantle. All of the novels require a fair bit of research, but it’s research I enjoy, and it doesn’t seem segregated from my experience of the present when I walk around the streets of Fremantle, or in conducting the research for The Sawdust House, the streets of Cork city, London, New York City and San Francisco. This is because in inhabiting the world as a writer, whether I’m at my desk or not, I’m constantly wondering while wandering. Constantly thinking of and imagining the lives that belonged and belong to the buildings, streets and landscapes that I pass through.

I am lucky enough to belong to a family of storytellers. My grandparents’ generation filled my young mind with stories of early Perth, and when pressed, my mother and father are always happy to yarn about their early lives and those of their extended family. It quickly became apparent to me, as a kid, how extraordinary many of these lives were – extraordinary and ordinary at the same time. I have always had a melancholic nature, especially as a child. It seemed sad to me from an early age that those lives and those stories would pass away into nothingness with the passing of my parents and grandparents, and eventually my own passing. I also wondered as a child about the ancestors that nobody could remember anymore, whose lives were gone but whose stories were gone as well. I think that this early wonder at others’ lives, but mostly sadness at the loss of important stories, was a great spur to my childish imagination, and it’s something that continues to this day as I walk through the city streets or the landscapes outside the city – imagining the lives that belonged to this place, and every place. If I know some of the stories, then it feels like I inhabit the world in a fuller way, and that the world around me has more texture and more meaning.

But what does this mean for my writing?

Writing fiction, of course, means living with ghosts of my own making (even when some of them are based on historical figures) and spending a lot of time in their company. As a younger writer, I was very influenced by Kim Scott’s early approach of using fiction to write into gaps in the historical record. I’m generally looking at gaps in a very different kind of history, but the approach is something that is useful – aiming to use the persuasive and immersive tools of fiction to fill out a picture that contains plenty of silences. Fiction, in its paradoxical way, can certainly feel like the truth, and by way of condensing and reordering, it can also be truthful to the historical record. This is something that I find attractive when inspired by curiosity to research into a singular historical figure – as in the case of The Sawdust House – or into historical practices and the enforced silences around them, as is the case with much of my Perth-focussed crime fiction. This mix of presence and absence in the historical record is what I find initially fascinating, and then, when it comes to writing, questions of relatability and contribution to broader narratives become important. In this case they led to questions about early convict history and the largely unknown but important Australian contributions to the American story.

Who is Yankee Sullivan and how did you go

about researching his life?

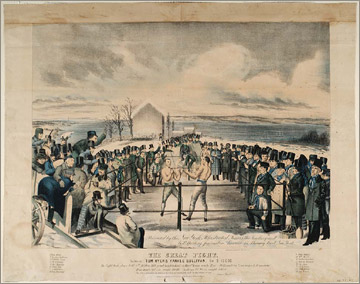

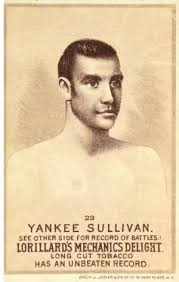

The Sawdust House follows the life of James ‘Yankee’ Sullivan, an escaped Irish-Australian convict who became a ‘notorious man’ in the Gangs of New York milieu, and a celebrated boxer, recounted from his San Franciscan prison cell where he’s awaiting trial. I first came upon the character of Yankee Sullivan while researching my earlier novel, The Coves (2018), which was set in 1849 gold-rush San Francisco, featuring the largely unknown story of how a cast of Australian criminals had taken over organised crime in the nascent city, until they pushed things too far and a vigilante committee was organised to rout them from the town. The routing was unsuccessful in the first instance, and ‘Australian’ became something of a dirty word in California, a synonym for all kinds of vice and depravity. The character of Yankee Sullivan played a small role in The Coves, but I sensed there was more to his story than the lurid media accounts and self-mythologisation he employed (understandably, as an escaped convict), and this was confirmed to me when I began to dig deeper. Nobody seemed to know his real name, for starters, but with a bit of detective work I was able to learn much of his early story, beyond the figure that he cut in the US of the colourful rogue, which just made him more interesting to me. I discovered his court records at Old Bailey Online (a terrific resource for researchers), and the writing began to follow the amateur sleuthing from there.

Why did you structure the story the way you have?

The Sawdust House is less about boxing and more about the joys of storytelling, as Sullivan recounts his difficult and yet extraordinary life from his prison cell. My aim in writing the novel wasn’t just to inhabit a character, or characters, but a kind of language – a hybrid version of the loose, indeterminate and polyphonically evolving English of the mid-nineteenth century. For me, this was the pleasure of both the research, but also of the writing. I wanted to start from the position of Yankee Sullivan, in a San Franciscan prison cell; a man who’d lived rich lives in four different countries, who had a vivid public persona but also a troubling personal history of poverty and institutional abuse, whose past and immediate future are crashing together. I wanted the structure of the novel to reflect this fracturing and unpredictable flowing of thought, moving backwards and forwards through time but also towards and away from his engagement with his main interlocutor, Crane. I wanted to approach his understandings and his experiences somewhat aslant, as a reflection of his position and psychological state, and the structure I chose seemed to do that best.

What other works of historical fiction does

The Sawdust House resemble?

Structurally and stylistically, I think the novel falls somewhere between that of Tom Franklin’s Hell at the Breech, Michael Ondaatje’s The Collected Works of Billy the Kid, Ian McGuire’s The North Water and Peter Carey’s The True History of the Kelly Gang.