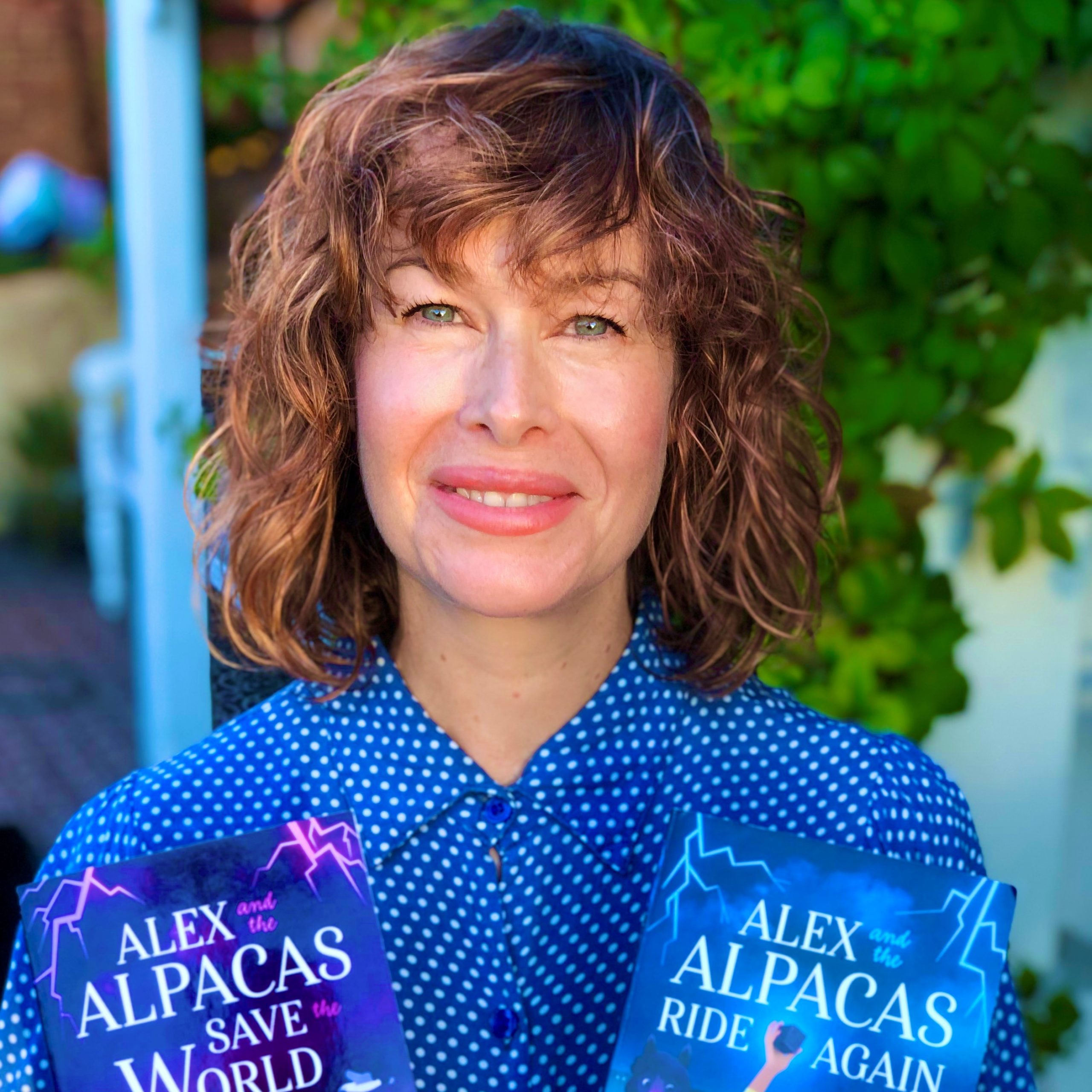

Alex and the Alpacas author Kathryn Lefroy on writing for readers who don’t want to read

I am not a reluctant reader. Quite the opposite, in fact. For as long as I can remember, given the choice between just about anything and a good book, the pages always win.

And yet somehow I write books that engage reluctant readers. I didn’t set out to do this – I didn’t even realise I did it until several parents pointed it out to me. But that made me take a step back to examine my writing forensically so I could better understand what I do to engage readers who might not want to read.

Empower them to want more with short chapters

I got an email from a parent once thanking me for writing a book with short chapters. They said it was such a relief, come bedtime, that they could read a chapter of Alex and the Alpacas Save the World to their kids and still have time for a glass of wine and an episode of Netflix after the kids were asleep. They also said that if the kids were particularly good that evening (less of the ‘I don’t want to clean my teeth’ and ‘I’m not tired’) they would give them a special treat: TWO CHAPTERS!

I don’t know that these kids were unenthusiastic readers, but that email got me thinking. Regardless of how old we are, we always want more of a good thing, don’t we? It’s true for chocolate covered almonds (or glasses of wine), Netflix episodes and book chapters.

Keeping reluctant readers engaged is about hooking them with your stories, sure. But I think it’s also about empowering them to want more – igniting that spark in them to want more. Short, sharp chapters can not only save parents’ sanity, but can also entice reluctant readers to reframe their thinking about books – they start requesting to read (or have read to them) more, rather than looking at each chapter like some particularly cruel form of literary punishment.

Write children’s books that don’t make adults want to poke their eyes out

For many kids who don’t want to read, their best access to books is via the adults who read aloud to them. And if you’re a grown up, you most likely don’t want to spend your time reading a book that causes you to roll your eyes and scoff, ‘You cannot be serious?!’ every two minutes. In fact, one of the nicest messages I’ve received was from a parent who said, ‘Reading your book to my kids every night doesn’t make me want to poke my eyes out – thank you.’

I think that comes from the fact that, when I write kids books, I’m not actually writing ‘for kids’. I write stories that I want to read using language that I find interesting. And yes, many of those stories just happen to involve talking alpacas, ancient spirits and possessed Tasmanian tigers. But they’re also built on universal themes that appeal to a lot of people, regardless of age or where they sit on the bookworm spectrum.

Shift gears

When people think about hooking readers – especially readers who don’t particularly want to read – they often think more explosions, more aliens, more car chases! More, more, more! But too much of a good thing … well, it can be too much. Like, if you eat that entire passionfruit, lime, and coconut sponge cake it’ll stop tasting good after a while. Similarly, if you fill a book with nothing but car chases and explosions, those will cease to be interesting after a few chapters.

Give your characters – and your readers – a chance to take a breath by alternating high-energy, high-octane scenes with quieter moments. You get to choose how and when and why you do this, but remember that variety is the spice of life. Even reluctant readers want to spend a little time just hanging out with your characters when they aren’t in mortal danger.

Make it a movie … with words

When I was ‘learning’ how to write books I was also ‘learning’ how to write screenplays (full disclosure: I’m still learning the art and craft of both, and always will be). These days, I split my time between writing novels and film scripts. Maybe because of this (or because I’m a sucker for big, commercial stories) my books are structured a lot like a Hollywood movie.

It’s a structure that 99.9% of kids are familiar with, so even kids who don’t naturally gravitate toward books can be drawn into the story. Even if they don’t know the signposts to look out for (first act break, climax, second act turning point, etc.), they can instinctively sense when certain things should happen because they’ve seen it before on screens. They’ll stay with you because they’re waiting for the big scare, the heartwarming reunion or the hint of death – even if they don’t specifically know that’s what’s coming. It’s familiar. It’s comforting. It makes us feel smart when we can anticipate what’s coming up.

You might think that this makes for a boring story, but I don’t think that could be further from the truth. Just because the structure is familiar, doesn’t mean the details should be. In fact, the more rigidly you stick to structure, the more fresh and unique the specifics of your story should be – that’s the fun part where you, the writer, get to play around and break stuff. But by presenting stories to reluctant readers in a format that makes sense to them, you’re more likely to keep them with you for the journey.

These are by no means the only ways that you can get those not-so-eager-beaver readers invested in your stories. But doing the above helps me not only craft stories that appeal to broad audiences, it also lets me have a lot of fun as I’m writing them!