Two books that ask: can we be better than this? – and why the answer is YES

True stories in the real world

As a publisher and editor, I am an active participant in the creation of books other people will read. The fiction I edit can connect readers to inner words, the non-fiction to the ‘real world’. And some of those stories can be a long time in the making.

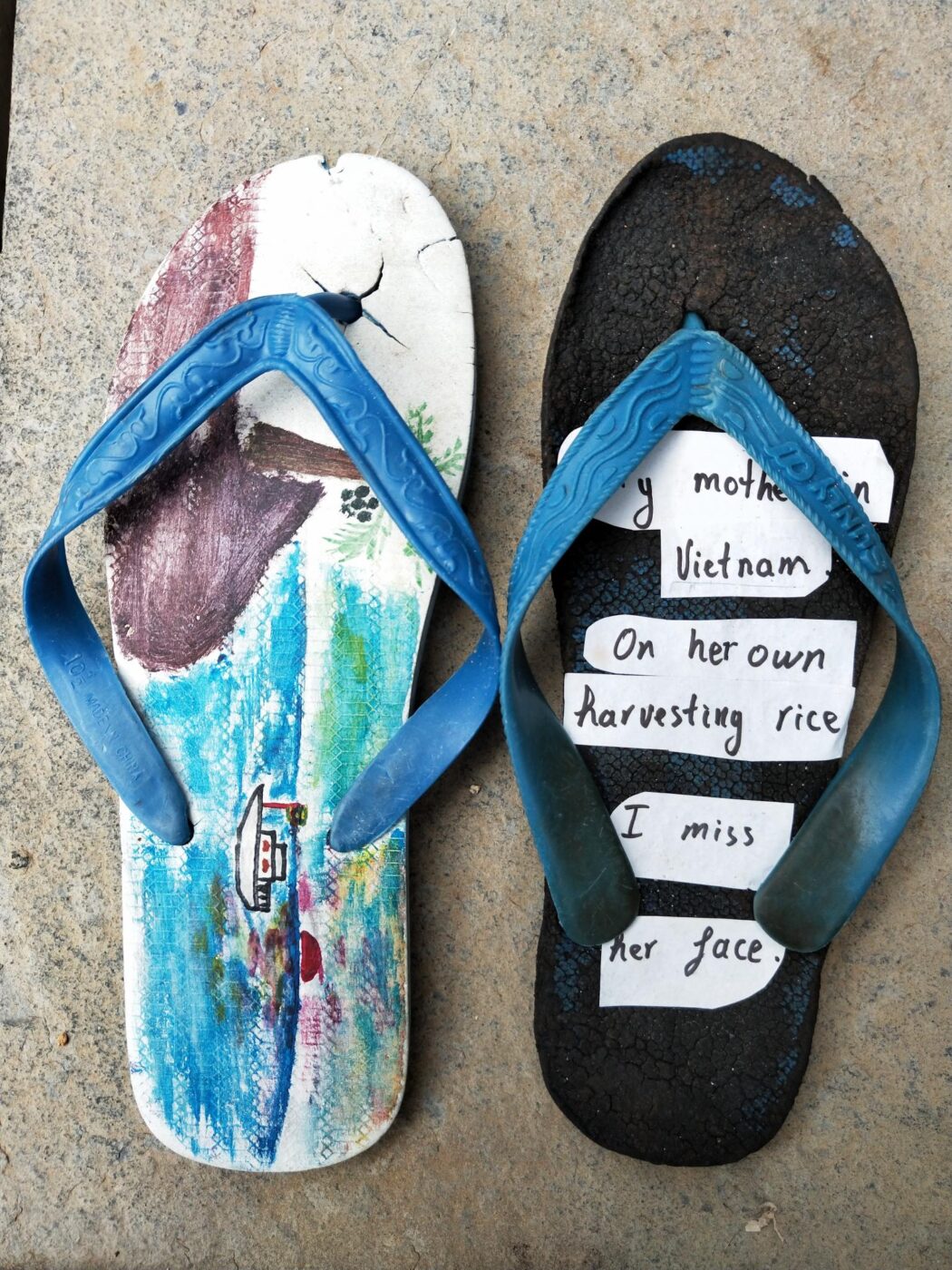

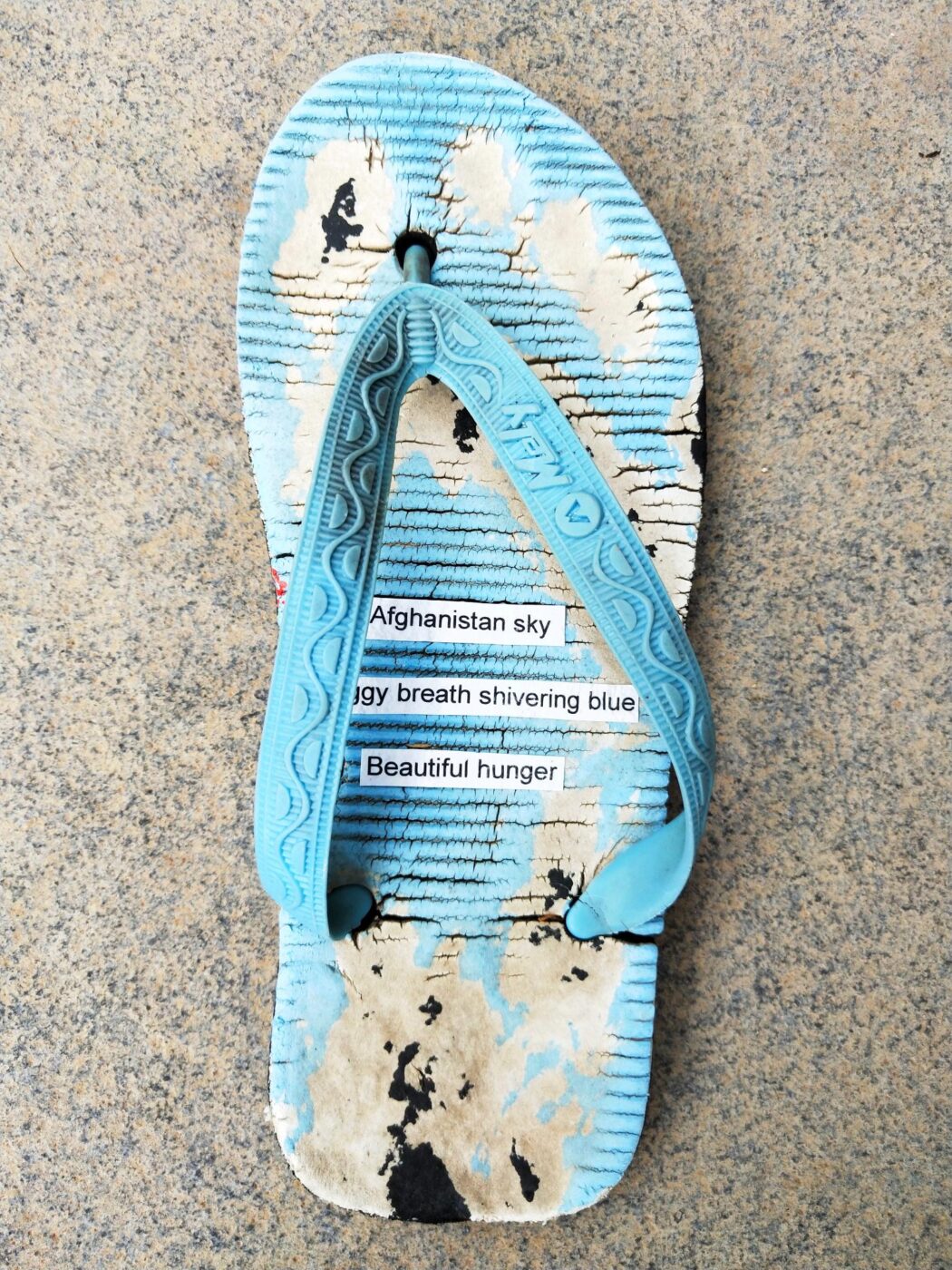

In 2011, Fremantle Press assisted poet Reneé Pettitt-Schipp with a poetry exhibition she was bringing to Perth from Christmas Island. The exhibition was called Thonglines, and it featured poems pasted on thongs washed up on the shores of Christmas Island. The poems were written by asylum seekers Reneé had taught in immigration detention. They were written in a language that was not their own, after desperate journeys the asylum seekers had never wanted to take. They were heartbreaking to read, each poem a fragment of distress and dislocation lying almost beyond the scope of comprehension.

When Reneé worked as a teacher in immigration detention on Christmas and Cocos (Keeling) Islands, the things she saw there came to fill her with big questions:

Though I chose to step away from its paradisaical shores, the troubled landscape of the Indian Ocean Territories never left me. This world of water lapped at my fringes night and day, bringing a relentless tide of questions, eroding beliefs about my country and who I thought I was … The story of the islands had become so irrevocably entangled in my own, that in 2016 I found myself boarding a plane back to the Indian Ocean Territories in order to make sense of my forever-changed life. What had I witnessed on the islands that I needed so strongly to make sense of? What was it, after five years, I was unable to accept and let go? Since childhood, I had understood my ‘Fair Go’ country as a place where everyone had an equal chance to work and thrive, and where each person’s inherent worth as a human would be upheld. Did I still believe in my ‘Fair Go’ nation after all that I had seen? (RPS, p. 6)

The answers to her questions became a book called The Archipelago of Us: A Search for Our Identity in Australia’s Most Remote Territories, which I edited with Reneé. The book tells a story not only of what went on in immigration detention but the recent human history of the archipelago itself – the gifts of living in a tiny interdependent community, and the deep scars created by racism and colonial occupation.

For Reneé, her archipelago questions sat on top of an earlier reckoning from when she had worked in the Kimberley in 2009. Reneé told me that time had ‘floored her’:

I had no hooks on which to hang the trauma (and equally, the incredible resilience) I witnessed in Muludja and Bayulu, two beautiful small communities just outside of Fitzroy Crossing. What I saw did not fit with my belief in my essentially compassionate country. At that time, I began to understand that Australia’s rhetoric (originally ironic) as being ‘The Lucky Country’ was deeply dishonest. Lucky for who? It may seem innocent enough to perpetuate positive views about who we are as a nation, but as we have seen in the violent threats made against Stan Grant and his family recently, if you dare challenge the innocent ideals of nationhood in Australia, the dark denial that sits behind these tropes can quickly surface. There is an extraordinary shift taking place at the moment, where many in our country are ready for a more complex view of history.

Aspects of a ‘complex view of history’ can be brought to light by a writer who bears careful witness – such as the experience Reneé relates in The Archipelago of Us about taking two asylum seekers out on a rare daytrip to see a waterfall:

Massom turned in a circle where he was standing, he raised his arms, raised them high and wide, turning and turning, laughing and looking at us in disbelief. He was exhilarated, standing in the jungle, with the wild sounds of the world all around him. I watched him, knowing something incredible and important was happening, a shift I had started to believe was not possible. He turned and whooped, beaming with joy, and all I wanted to do was watch, to be filled with the wonder of that moment, watching everything in Massom spark and glow … I wondered how far this scene must have felt to the men from the concrete and steel of their respective detention centres … Years later, writing from Melbourne, Massom will tell me this was one of the best moments in his life. (RPS p. 98)

I asked Reneé whether she thought that books like hers can truly change the way people see the world. She believes the answer lies not in the writing but in what happens when such stories are received:

I don’t think anything I write will make any difference unless it wakes up something that already lives in the reader. If my work wakes up the love, the passion, the drive that lives in the reader, then yes, our stories can change the world! I had the most beautiful experience on the weekend of launching my book in my local community. I took the risk of reading a devastating story from The Archipelago of Us, followed by a short excerpt depicting a moment of pure joy. The space became electric, it was incredible! After I read, it was like each person became a gently glowing light. People were laughing, quietly crying or talking tenderly to each other – the bookshop became a room full of love. I believe if my work had been making a logical case for the better treatment of asylum seekers, that seemingly transcendent moment would not have taken place. Stories cut through our confirmation bias where we seek facts that support what we already believe. Well-crafted stories bypass our filters and make a beeline straight for the heart.

How could it be otherwise?

Like Pettitt-Schipp, Torres Strait Islander man and Indigenous leader Thomas Mayo understands it is ‘the personal stories that really enfold you in the truths of a great national tragedy that is still playing out through intergenerational trauma’ (TM p. 26). His stories of hope enfold the reader in the same way.

Mayo’s Finding the Heart of the Nation is the story of his own journey to Uluru in 2017, along with interviews he conducted with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people about why they support the Uluru Statement from the Heart – a document created from multi-tiered dialogue and consensus from representatives from lands ‘covering the entire continent and adjacent islands, and the lands of all Indigenous First Nations’ (TM, p. vi). Mayo has also written some books for younger readers to share the message of the Uluru statement.

Mayo’s most recent work, The Voice to Parliament: All the Detail You Need, was written to ‘counter misinformation’ (TM p. 6). It is a proposed antidote to ‘the torment of our powerlessness’ described in the Uluru Statement. This book describes why Indigenous people want a Voice to Parliament enshrined in the Constitution. The request for a Voice is a modest request to connect 60,000 years of continuous culture and heritage to the modern world.

Thomas Mayo has travelled the length and breadth of the country to speak about the Uluru Statement. He continues to travel to speak about the forthcoming referendum which is, as he described, ‘an invitation, an opportunity, and the most important campaign of the lifetime of Australian and Torres Strait Islander people’.

In May, I was fortunate to hear Thomas speak in the Wetlands Centre at Walliabup. At the end of his talk, Mayo repeated from memory the Uluru Statement, looking at each of us as he spoke aloud. His soft voice embodied the hours of conversation that led to that declaration, the statement of intention requesting Voice, Truth and Treaty.

I repeat it here in full because if you have not read it yet, I think it is important that you do.

The Uluru Statement from the Heart:

We, gathered at the 2017 National Constitutional Convention, coming from all points of the southern sky, make this statement from the heart:

Our Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander tribes were the first sovereign Nations of the Australian continent and its adjacent islands, and possessed it under our own laws and customs. This our ancestors did, according to the reckoning of our culture, from the Creation, according to the common law from ‘time immemorial’, and according to science more than 60,000 years ago.

This sovereignty is a spiritual notion: the ancestral tie between the land, or ‘mother nature’, and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who were born therefrom, remain attached thereto, and must one day return thither to be united with our ancestors. This link is the basis of the ownership of the soil, or better, of sovereignty. It has never been ceded or extinguished, and co-exists with the sovereignty of the Crown.

How could it be otherwise? That peoples possessed a land for sixty millennia and this sacred link disappears from world history in merely the last two hundred years?

With substantive constitutional change and structural reform, we believe this ancient sovereignty can shine through as a fuller expression of Australia’s nationhood.

Proportionally, we are the most incarcerated people on the planet. We are not an innately criminal people. Our children are aliened from their families at unprecedented rates. This cannot be because we have no love for them. And our youth languish in detention in obscene numbers. They should be our hope for the future.

These dimensions of our crisis tell plainly the structural nature of our problem. This is the torment of our powerlessness.

We seek constitutional reforms to empower our people and take a rightful place in our own country. When we have power over our destiny our children will flourish. They will walk in two worlds and their culture will be a gift to their country.

We call for the establishment of a First Nations Voice enshrined in the Constitution.

Makarrata is the culmination of our agenda: the coming together after a struggle. It captures our aspirations for a fair and truthful relationship with the people of Australia and a better future for our children based on justice and self-determination.

We seek a Makarrata Commission to supervise a process of agreement-making between governments and First Nations and truth-telling about our history.

In 1967 we were counted, in 2017 we seek to be heard. We leave base camp and start our trek across this vast country. We invite you to walk with us in a movement of the Australian people for a better future.

When Mayo stops speaking, we are quiet. Later we move outside to stand in the sunshine and a woylie appears from the swamp grasses to hop amongst us – Walliabup is ‘place of the woylie’. Its presence is its own kind of blessing.

Stop. Listen. Learn.

Enshrining a Voice in the Constitution is one way we can move forward together. But after more than 230 years of dispossession, in minute and monumental ways, there is much ground to make up. I am learning this all the time, often from missteps I take.

Recently, I was working with a Gunditjmara author who would not respond to my increasingly urgent emailed requests and accompanying deadlines as an anthology drew near to print. In the end, after advice from a mutual colleague, the author and I dealt with them all via phone – a conversation in which I could introduce myself to him and he then readily responded to me.

At the end of our call, that author himself raised the matter of his delays in replying to me.

‘Why am I so recalcitrant?’ he asked me, laughing. ‘Because of the invasion perhaps?’

It was a joke about my whiteness and my insistence, and suggestion that there is another way to do these things. His cheerful patience was humbling. I have seen it many times in First Nations authors – and wonder if that might be a self-preserving way to step lightly over centuries of devastation.

Introduce yourself first is one of the things I have to keep learning.

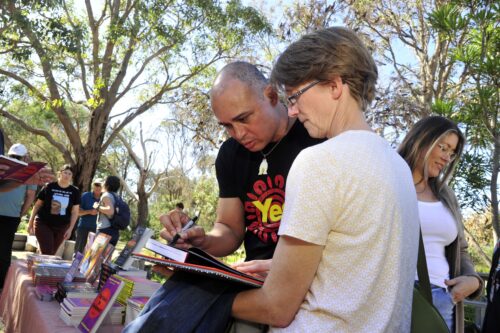

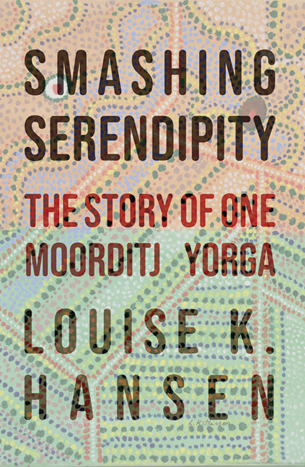

In late 2021, I was all set to get down to business, but ‘Take your mask off! Let me see your face!’ said author Louise K. Hansen the day I met her during COVID, before she and I began work on her memoir, Smashing Serendipity. Then when my face was revealed, she said, ‘Now, who are you, and where are you from?’ She reset the meeting on better terms so that our working relationship could properly begin.

Let yourself be seen and known.

‘You wadjelas keep asking questions,’ Louise’s daughter told me just yesterday. ‘You dissect everything.’

Listen before you speak.

Wadjela writers (not just editors) need to think about doing things differently too. Reneé observes:

With the work I have been doing through my Regional Arts grant with Elders in the Great Southern, I consult about everything I do, from the culturally significant places I write about, through to any Noongar language or place names I use. Enormous damage can be done if we ignore this etiquette. Recently, I was asking Menang/Merningar Elder Lynette Knapp for her permission to write about boorna gnamma (Indigenous water trees) for our local paper. She said, ‘You go girl, I am so proud of you.’ That kind of endorsement meant so much to me, but I believe Indigenous support comes from the building of trust. Trust is built through genuine respect for others, and consultation is an inherent part of being respectful as a writer.

The extraordinary power of unbroken stories

True stories are the most powerful tools we have. Indeed, it is an unbroken chain of stories that has ensured the oldest culture on earth. The Noongar people of Walyalup – like Aboriginal and Tiwi Islander people all around the country – have stories that describe the rising of the sea level that took place 7,000 years ago when the ocean cut off Wadjemup (also known as Rottnest Island) from the mainland, including Walyalup (Fremantle). Marine geographer Patrick Nunn and linguist Nicholas Reid believe that twenty-one Indigenous stories from across the continent accurately record events like this between 18,000 and 7,000 years ago, when the sea rose 120 metres. It is the multi-generational commitment to oral storytelling that has generated faithful reproduction. Reid says:

When you have three generations constantly in the know, and tasked with checking as a cultural responsibility, that creates the kind of mechanism that could explain why [Indigenous Australians] seem to have done something that hasn’t been achieved elsewhere in the world: telling stories for 10,000 years.

Humans have always told stories about events and places. But the way that place connects with a person can also shape one’s way of being in the world. When we pay attention, meaning flows in both directions. Reneé described her experience this way:

Writing the book meant I had to listen to others, to their deepest and most affecting stories. But, as I also learnt from the extraordinary late Australian writer, Ross Gibson, it also meant listening to Country. That kind of deep listening, that presence, took everything in me to maintain each day during my return to the islands in 2016, and at night after finishing my notes, I would often fall into bed completely exhausted. But by the time I finished my research in the Indian Ocean Territories, I was exhilarated. I was happy in a way I did not know was possible … I think when I first went to the islands, I thought I was in control of my life and that I could save people. The islands throw you up hard against your own powerlessness and mortality, you are forced into a new humility by the wildness of the terrain.

When I started losing the people I loved [during this time], I was forced to accept that I could not save anyone, that the things that played out there and elsewhere were so much bigger than me and my sphere of influence. I was heartbroken. But in this process, there was a kind of relinquishing, and when I returned to the Indian Ocean Territories having had the sense of my own importance shattered, this shift allowed me to deeply connect with others and the world around me, I was opened. I had found a new and more expansive way of being a person in the world based on a deep understanding of my own interdependence on the human and more-than-human world.

The courage to sit in discomfort

It can be uncomfortable to disturb the status quo. But, as a beloved teacher I knew once observed: ‘When we are most uncomfortable, that is when we are learning.’ And I wonder, what is there to be afraid of in a request from others to be heard, or in a simple poem pasted on a washed-up thong?

‘Australia needs to hear and understand its own story,’ Reneé says. ‘We are a nation born from blood, from the murder and dispossession of our First Nations people. When we can face this fact squarely, we pave the way for a very different – and far more hopeful – future.’

Thomas Mayo speaks of a ‘Fair Go’ – in this case, voting yes in a referendum to enable ‘a unifying nation building act of reconciliation’ (TM, p. 54). In The Archipelago of Us, Reneé also returns in her conclusion to the idea of a ‘Fair Go’ too:

Perhaps it is in learning to see and remember, even when the remembering is difficult, to listen and be attentive, not only to each other but to Country itself, that real change can come about. And how can we imagine our country? … Can we as a country be courageous enough to stretch our definition of ‘Australian’ to become more supple, more bountiful and open? Can white Australians collectively show a willingness to finally turn and fully face the violence with which the nation was forged? If we as citizens could find this less fearful version of who we are as people, as a society, perhaps the ideal of a ‘Fair Go’ Australia could finally guide us – perhaps it is precisely what we need. (RPS, p. 290)

Such books remind me to keep my eyes and ears open to true stories of people and places – whether I am working with their author or reading them once they have been written.

Both these books are invitations to become better versions of ourselves by posing questions that take courage to answer. And both contribute to the story of who we are by sharing a dream of who we might become.

References (in order of appearance)

Pettitt-Schipp, Reneé. Thonglines: Thong poems by asylum seekers. 2011, Denmark Festival of Voice.

[RPS] Pettitt-Schipp, Reneé. The Archipelago of Us: A Search Our Identity in Australia’s Most Remote Territories, Fremantle Press, 2023.

All other quotes drawn from an interview with Reneé Pettitt-Schipp. 29 May, 2023.

[TM] Mayor, Thomas. Finding the Heart of the Nation: The Journey of the Uluru Statement towards Voice, Treaty and Truth. Hardie Grant, 2019.

Mayo, Thomas and Blak Douglas. Finding Our Heart: A Story about the Uluru Statement for Young Australians. Hardie Grant, 2021.

Mayo, Thomas and Rosie Smiler. Freedom Day: Vincent Lingiari and the Story of the Wave Hill Walk-Off. Hardie Grant, 2021.

Mayo, Thomas and Kerry O’Brien. The Voice to Parliament Handbook: All the Detail You Need. Hardie Grant, 2023.

Mayo, Thomas. Presentation at Beeliar Wetlands Centre. 20 May 2023.

‘View the Statement’. The Uluru Statement from The Heart, https://ulurustatement.org/the-statement/view-the-statement/

Robertson, Joshua. ‘Revealed: how Indigenous Australian storytelling accurately records sea level rises 7,000 years ago.’ The Guardian, www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2015/sep/16/indigenous-australian-storytelling-records-sea-level-rises-over-millenia

Hansen, Louise K. Smashing Serendipity. The Story of One Moorditj Yorga. Fremantle Press, 2023.