When Georgia Tree snagged a place on the Fogarty Literary Award shortlist, little did she know she’d soon be a published author with her very personal book about family

When I finished my creative writing degree, I wasn’t sure I ever wanted to write again. I had half a collection of short stories that I couldn’t bring myself to finish. Obsessed with the idea of a ‘real’ job, but working a part-time/shitty retail gig, I looked back at university as a fun but largely pointless piss-up, and my second-class honours thesis as an embarrassment.

Around this time, Australia chose a new Prime Minister. Though I’d always been interested in politics, it took the election of Tony Abbott to high office – a man who believes in men’s genetic predisposition for such high office – for me to join the Labor Party. I volunteered and worked for Labor politicians and enrolled in a Master of International Relations. I was, and am, content with working towards/for governments that support a more equitable society.

It took my aunty and grandmother dying in close succession in 2016 for me to realise the opportunity cost of not writing their stories.

Joyce Bailey (nee Mitchell) was born in 1925 in the Nullarbor town of Cook, South Australia. She lived her life along the Trans-Atlantic Railway, where she met her husband Malcolm – raising their children in railway town Port Augusta, and later Kalgoorlie, Western Australia. She sang opera over the wireless on the ABC. She served in the Airforce. She lived with diabetes, or as she called it, the ‘sugar’, but still made the best custard in town. She was a little bit racist. She outlived her husband and saw three of her own four kids and a granddaughter die before herself.

I loved Nan, and I loved hearing her stories.

Her death brought with it the death of her small piece of Australian history. Her homemade pasty recipe – gone forever.

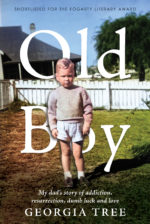

This compelled me to write Old Boy. But recording this history meant telling my dad’s version of the stories of family members who are very much alive.

Prince Harry’s ghostwriter JR Moehringer, recalls working with Andre Agassi, who enquired as to how you ‘write about other people without invading their privacy’. In which the memoirist responded: ‘Sometimes, in order to tell the truth, you simply can’t avoid hurting someone’s feelings.’

But the thing about truth is, it’s untrustworthy. Memoir and memory are malleable.

I chose to write Old Boy from my dad’s perspective. It would be a completely different book if written from another voice. I structured the narrative like a novel, rather than a biography. It’s the Hollywood version of my dad’s life. Which means there needs to be a villain. But everybody is the main character, and nobody is the villain in their own story.

I often reference Netflix’s The Crown when explaining the book: if Old Boy is The Crown, then my other (living) grandmother is the Queen. She’s a caricature of herself in the text, portrayed as cold and uncaring. This representation displays a complete lack of empathy for her situation. She was raised in a modest home dominated by a father suffering post-war PTSD. She survived polio. She married a man who spent more time at the pub than with his young family. She went through a divorce in the 1960s, when Perth was still a small town and divorce was still an uncommon and shameful thing. For Joss, I’m sure that leaving her three young children in the care of their grandparents while she worked to provide for them, was the only realistic option. It was only for two years. But for children, that small, two years felt like a lifetime.

Writing (and subsequently publishing) Old Boy has been an emotional and, at times, painful experience. Balancing the integrity of my understanding of the narrative with the broader family history was (and still is) precarious. I haven’t always had the balance right. I am frustrated by generations before me who have fostered a pervasive silence when it comes to trauma. At the same time, I empathise with their place in a system where silence is a means to survive. The world is better served with such empathy, and an ability to reflect on our actions. I can admit I fucked up. If I had my time again, I would have made better choices.

But isn’t that the human condition?

There’s no redemptive arc without the fuck-up in the first place.