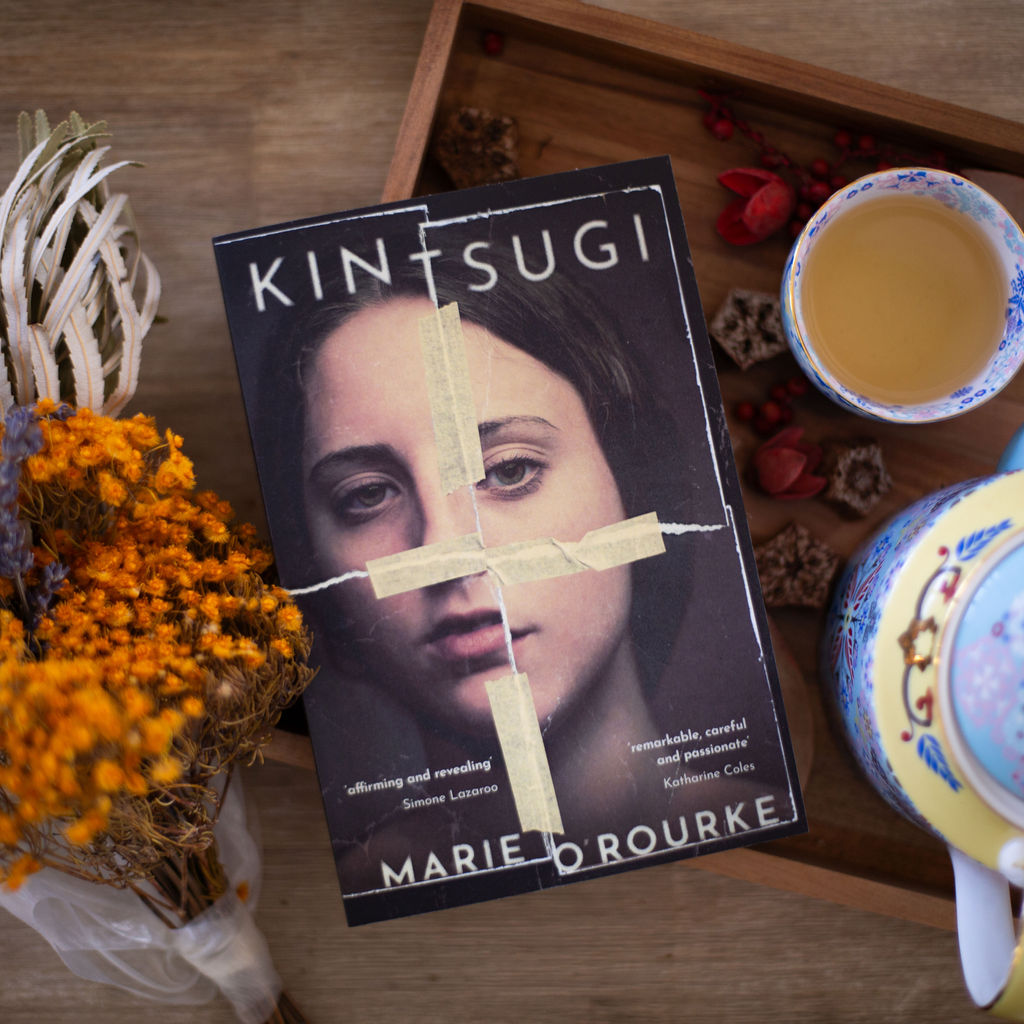

Dr Daniel Juckes says Marie O’Rourke’s debut book of essays, Kintsugi, is the feeling of memory itself

Associate editor of Westerly Magazine, Dr Daniel Juckes, launched Kintsugi by Marie O’Rourke in Fremantle this month. With exquisite prose, Marie reflects on the beauty of brokenness and the ways in which time can transform our understanding of the past. But there’s so much more to this wonderful collection of essays, as Daniel explored in his launch speech below.

It is not often that you get to share in the journey of a book, and this is one I have been able to do just that for. To see it now, all printed, covered, and glorious, is a tremendous and almost uncanny joy.

I first met Marie when we were at very similar points in PhDs which, as anyone who has done one will attest, are all kinds of difficult. We were trying to figure out what our research would be about, and how we might conduct it. Even, probably, what research was. Marie’s friendship was so important in my own getting through that degree. And I always knew, and always told her, that her words would reach this point. I am so glad that they have. The truth was in them even as she wrote them.

I can still remember the first time I read some of Marie’s work. This was in a writing group at the university where we studied, and the piece was an early version of the essay which would become ‘Add It Up’. This short work, even now, helps me contemplate what Marie’s writing does; how it functions; what it is concerned with. It is those three things I’d like to talk with you about this evening.

Needless to say, I won’t be able to do justice to a book like Kintsugi in the short minutes I have to speak: the point of an essay, and an essay collection, is the journey of it—the slow, unfurling consciousness of exactly that: consciousness. If the book works on us, we sink into the mind of someone else.

I hope, now, that I can communicate some of the power of Marie’s writing and of her book, which offers so generously the slick and deep mind of another, through its sequence of shadows, impressions, pressures and responsibilities—all of which it observes through the sidelong glance of the essayist. The early work I read had these qualities too, and they blossomed as Kintsugi became the thing you now can hold and read for yourself.

*

Marie’s writing process, which seemed to involve holding an essay in her head until its shape was there and its truth was clear, is one which I am in awe of: all those shadows and impressions circling; forming; threatening to drift. But then held thrillingly to the page! I’d like to share some of my thinking on those shadows first, which seem to echo one of Kintsugi’s key themes: memory.

In ‘Add It Up’, Marie quotes Nietzsche, who says ‘Blessed are the forgetful, for they get the better even of their blunders.’ Even within this one essay, though, so many of the tensions of memory are evident, so that we both doubt and believe Nietzsche at the same time: forgetting is hard, especially when memory is so unpredictable, so embodied; the lure of memory somehow beguiling; a trap we all fall prey to. ‘Memory pulses through flesh’, Marie writes, and, ‘Muscle memory is more than repetitive tasks burned into the brain. It is the moments held in a fingertip, embedded in flesh, bound in skin which goosepimples to the touch.’ In this sense, we are held back by our memories, just as we are helped by them. And we are our memories, because we live whenever they recalibrate.

This feeling of embodied recalibration emanates from Kintsugi; it is the feeling of memory itself: the aliveness of this thing we all have, which is inherent to how we think and do, and which is what Marie’s writing revels in.

It is Marie’s commitment to the poetics of memory—perhaps to the verisimilitude of remembering—that takes her works into all the territories it ventures into—there are darknesses here, yes, but stilling the curves and contours of axons and synapses lets her show the complex, glowing contradictions of the act of looking back. This means that there is light as well, making this a volume that glows with force and emotion, just as it does with beauty and art. Driving all this is the body itself, which is a force of its own. As Ross Gibson points out, remembering is literally re-membering; putting the body back together; Kintsugi offers a similar kind of function, so that, through all the different kinds of grief we might encounter as human beings, the speaker is consistently, beautifully, complexly whole; she survives, survives, with scars that allow her multifaceted self to be.

All this stems from the perspective of that important, sidelong glance. The narrator in an essay called ‘Chiaroscuro #1’ peeks around doors; glimpses things lit by dark light. The reader—we, us—does too. And while the aim of this particular essay is ostensibly to tell things straight, the angle of viewing is still one of glimpses. This is both an ethical perspective and a necessary one. It offers witness through the kinds of funnels Marie knows make up our experience; is one more way of showing memory. And the tension, as it is throughout the book, is one of the felt—bodies moving, breathing, turning—with the thought. Reflecting this tension is what Marie’s writing does, because that is what memory does, and Marie’s writing is memory: ‘Unnerving,’ she writes in ‘Collect/Recollect’, ‘to be dependent on electrical charge, relying on some sort of path burned through synapses which my brain continues to follow.’ But awesome, and an incredible tightrope to offer the reader. That that rope is offered tenderly, through the knowing essayist’s glance, is all the more impressive.

*

How all this works is a trickier question, and one I can only really conjecture at. But it is also a question which Marie actively considers over the course of her book. Alongside memory, another subject and formal shaper of Kintsugi is the act of reading and writing: these things are intertwined in the episteme of the book. Most noticeably, this is through Marie’s engagement with the works of literature which have shaped her life, from her reading of Middlemarch to her questioning of the limits of the form which she chose to write in: the lyric essay. She writes over these works in palimpsest. However, it is her questioning of, and use of, metaphor, that I’d like to explore for a moment or two. This is part of how her sidelong glance is evoked, and thus part of how Kintsugi performs its ethical poetics of remembering.

In ‘Collect/Recollect’, Marie writes, ‘All my life’s memories come in flashes and fragments […]. Some refuse to leave and constantly replay; others hover in peripheral vision, move in and out of focus or “wobble”, depending on when, where and why they are called on.’

Peripherality is shown through references to art, to craft, to diorama, to the sidelining of women by men, to looking through glass or in mirrors, to conversations about the nature of metaphor itself, and to the double exposures which can sometimes haunt pre-digital photographs (on the latter, Marie writes, ‘Where two different images are caught, competing, in the one frame […] I worked hard to make out the original forms within the resulting blur: both were there, even as neither really was. / It occurs to me now that our memories are a little like this: recalled and reshaped afresh […] every time we lay a second image alongside the original, details [blur] a little.’

There are, as well, glorious experiments of scale in Kintsugi, where the reader is asked to zoom in close and tight to things that glint or shine, before moving out to see a more complex, bigger picture. All this lets the works here exist in that wobble of real/not real; there/not there. ‘Sometimes,’ Marie writes, ‘simile, metaphor, are the only ways we can come close to touching, recreating an image, a sound, a mood for someone else to share.’ But, is coming close enough? That is a question the collection leaves you with. The answer, at least from my perspective, is that of course it is; and of course it isn’t. This is an example of reading being read, and one sign of the cleverness of this book.

Reading itself, again in the frame the book sets up—but I think literally too—is a consciously intimate act, in which one mind meets another: it is an act of sharing, just as writing is. By looking sidelong, Marie is able not to flinch, and to share truly. In Kintsugi, the lines between art and life are thus drawn and redrawn, so that we are shown to be creatures of the ways we look and see; creatures of the lenses through which we are drawn to look. And the aim of this work, which attempts to do the impossible, and still the contradictions of life on the page, is brave and generous in rising to that challenge.

*

I hope I have been able to touch on the question of what this book is concerned with through my address so far. I’d like to be a little more explicit on that now, because those concerns also help to shape Kintsugi, just as memory and metaphor do. What I want to add first is that this is, above all else, a very human book. All those emotions we bottle up, which boil up, which drive us and form us, are here. This is deliberate. In the opening essay, ‘The Weight of Words’, Marie writes, that she works ‘with a quote from Ander Monson pinned above my desk: “She wants to be in a way transparent. She is a vulnerability artist”. Embracing my vulnerability,’ she says, ‘my sensitivity, I’m finding that these alleged flaws of feeling things acutely and thinking too deeply are precisely what keeps me alert to the currents of emotion which pulse through, around and between people.’

Vulnerability art is no easy thing to manage, just as the task of actually fixing a life to the page is an impossible one. But without facing the contradictions inherent in our human shapes, and, perhaps, without looking sidelong at those contradictions, one has no hope of doing that work; of drawing the lines of flights which exist through and between our selves.

When you read this book, a comingling will occur between yourself and Marie. Her art, and thus her vulnerabilities, will become your own. This is another, important, ethical choice: the writer does not have to do this, does not have to offer her soul in this way. But she does, because that is what her art demands, and what her ethics dictate.

The spectre of a flickering self which Kintsugi offers is thus a truer self: a self with flaws and scars exposed; through which are glimpsed heartbreak, grief and violence. But even while the book is a tribute to scars—and to flaws—it also pays deep homage to the jewels of life: to sisters, children, family, friends and love.

To finish: this is a wonderful book. It is honest, kind, tough, vulnerable and vivid.

I opened by describing my delight at seeing it published—I said the feeling was ‘uncanny’. This is because, for so long, this work, in its varieties, has been something which existed on hard drives and in conversation. Seeing it now, and being able to welcome it into the world, and also to be able to anticipate how it will move its readers, is a remarkable thing.

Kintsugi is available in all good bookstores and online now.

Daniel Juckes is a writer from Perth, Western Australia. He is a lecturer in Creative Writing at UWA, Editor at Westerly Magazine, Deputy Chair of the AAWP, and holds a PhD in Creative Writing from Curtin University. His creative and critical work has been published in journals such as Axon, Kalliope X, Life Writing, M/C Journal, Meanjin, TEXT, and Westerly.