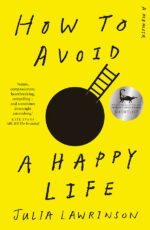

When the mother of beloved children’s author Julia Lawrinson died, she needed a way to deal with the avalanche of feelings – so began her memoir

How to Avoid a Happy Life is Julia Lawrinson’s story of a messy family legacy and a lifetime of extraordinary events that have to be read to be believed. Publisher Georgia Richter says, ‘Julia’s writerly superpowers of observation and analysis, along with a robust sense of humour, allow her to survive and then write about a childhood beset by anxiety and parental dysfunction, the murder of her best friend by a serial killer, Julia’s volatile marriage to her former female lover’s brother, and the tragedy and chaos of what follows.’ Earlier in the year Georgia interviewed Julia to get the story behind the scenes.

Why did you decide the write the memoir? Was it a different experience to writing your other books?

I started writing the memoir to try to make something out of the avalanche of feeling that rained down on me after my mother died at the end of 2019. I was overwhelmed by a grief about what I’d been hoping would be repaired or resolved before my mother died. I was also beset by feelings from my childhood that had been dormant for decades, and which surprised me in their intensity. So I started to write, because writing is always what I’ve done to make sense of anything.

Over my writing career I’ve fictionalised aspects of my life, but this was the first time writing a direct account of what happened to me. It felt very raw, and different to writing fiction for younger people. For a long time, I wasn’t sure whether I wanted to publish it. I found a mentor-for-hire who was in the US, Howard Norman, himself a brilliant memoirist and fiction writer, and I was lucky enough to be taken on by him. This helped in so many ways: firstly, he was in the US, so he was distant from the public things that have happened and knew nothing about my writing career, so he was approaching both me and the material fresh. Secondly, he had an uncanny ability to ask exactly the right question at the right point, like a good therapist. Thirdly, he could very kindly but insistently bring me back to the parts I really, really wanted to skip over – the parts describing my husband’s behaviour, for example – by telling me that the reader needed to know x, y, and z, which were things I couldn’t see myself.

What were the greatest challenges in the process? What surprised you?

The greatest challenge was facing up to all of my experiences in the writing of them – the good, the bad and the unbelievable. The chapter on Carita was written last because revisiting all of the Hillview hospital stuff, and then the unspeakably awful things that happened to her, was excruciating. But the only salve for it was telling a truth I could not have articulated earlier. And I wanted to honour the complexity of our friendship, the absence of which I feel to this day.

It was sometimes uncomfortable looking at myself as honestly as I could, not letting myself off the hook for the less than exemplary way I’ve sometimes behaved, not letting myself become embittered by the less than exemplary behaviour of others and hoping that I was striking the right balance in the writing in the service of the memoir as a whole. There is a lot I had to cut out because it was appropriate for therapy, not for a piece of writing. By the end, I felt more empathetic toward other people by virtue of trying to work out why they did what they did. We are all in this mess called life together, to riff on Georgia Pritchett’s memoir title.

The interaction of truth and memory and story was perplexing. Like all of us, I’ve told myself stories about my life which I believed, having repeated certain things often enough. For example, I always maintained my parents’ separation when I was nine didn’t affect me – not as much as some of the things that happened as a result of it, anyway. But having to write it, and therefore feel it, I find that I have minimised some things because their effects were more profound than I appreciated. It turns out I had learned certain coping mechanisms, for good or ill, through those formative years that I was completely unconscious of. It surprised me to learn how little one can understand oneself, despite one’s best efforts and a ton of therapy!

The best thing, though, was how much I enjoyed the actual writing, the laying down of sentences – being able to let myself write without calibrating my words for a younger audience was really satisfying.

What strikes the reader is the vulnerability of young women in this story. Do you think that things are different now from how they were when you entering your teenage years, and beyond?

‘Everywhere in the world, they hurt little girls,’ said Cersei Lannister in Game of Thrones, and unfortunately, that’s not just a line from a fantasy franchise.

Some things are same-same-but-different. There are no fewer deaths from domestic violence, and the courts don’t have fewer cases of child abuse, and now we have the head-mangle of social media to contend with. The existence of the dark web means that predatory men have far more avenues to find and exploit victims. While there is a fantastically active consumer movement in mental health, I am still aware of many stories from mental health facilities that suggest they can still be unsafe places for young people in particular.

On the plus side, we are beginning to have more language for abuse, and people are more able to speak about their experiences, in part thanks to social media. There are activists here in Australia like Rosie Batty and Grace Tame who have changed the language about particular types of abuse, and there are countless women working in various communities who are standing up to violence at the local level. Discussions about consent are just beginning: I hope these will change things as well.

Also, I’m very glad that hitchhiking isn’t an activity that young women do these days. Even at the time I knew it probably wasn’t a good idea, which didn’t stop me from doing it!

What advice would Julia Lawrinson today give to the younger Julia?

You’re stronger than you think you are.

What’s next for Julia Lawrinson?

I feel quite free, now I’ve done something I never thought I could (i.e., write a memoir). So my next project is a children’s verse novel set in 1907 in the Goldfields. After the battle of wrestling with content, it’s pleasant to be wrestling instead with form!

How to Avoid a Happy Life is available in all good bookstores and online. It will be launched on Saturday 11 May at the Literature Centre.

To hear more about Julia’s life, her podcast shares the materials that DIDN’T make it into the book.